What Is Peak Force and Why Does It Matter in Rehabilitation and Performance?

Team Meloq

Author

In the fields of sports physiotherapy and performance, we often talk about explosive power. A key component of this is peak force. It represents that single, instantaneous moment of maximum effort.

Consider a sprinter launching out of the starting blocks or a basketball player landing after a dunk. That split-second, highest point of force they produce or absorb is their peak force. It's a vital snapshot of an individual's maximum strength capacity during a specific action.

Decoding the Meaning of Peak Force

Imagine listening to a powerful sound system. It plays music at a comfortable, average volume, but then a deep bass note hits. For a fraction of a second, the system reaches its absolute maximum output. This is a useful analogy for peak force in human movement.

It’s not about the average effort over a period; it's the absolute zenith of force generated in an instant. This single data point is crucial for understanding how well an individual can perform explosive movements and, equally important, how they manage high-impact loads. For foundational knowledge, our guide on what force measurement is is a great place to start.

For a quick reference, here's a simple breakdown of what peak force and related concepts are about.

Key Force Concepts at a Glance

| Concept | Simple Explanation | Common Unit of Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Force | The single highest point of force produced during a movement. | Newtons (N) or Body Weight (BW) |

| Ground Reaction Force | The force exerted by the ground on a body in contact with it. | Newtons (N) or Body Weight (BW) |

| Rate of Force Development | How quickly an individual can produce force. | Newtons per second (N/s) |

This table helps put the core idea into perspective. Peak force is just one piece of the puzzle, but it is a significant one.

A Key Metric in Biomechanics

In biomechanics, peak force is defined as the highest instantaneous force recorded during a movement. It serves as a primary marker for both performance capacity and the magnitude of stress the body experiences.

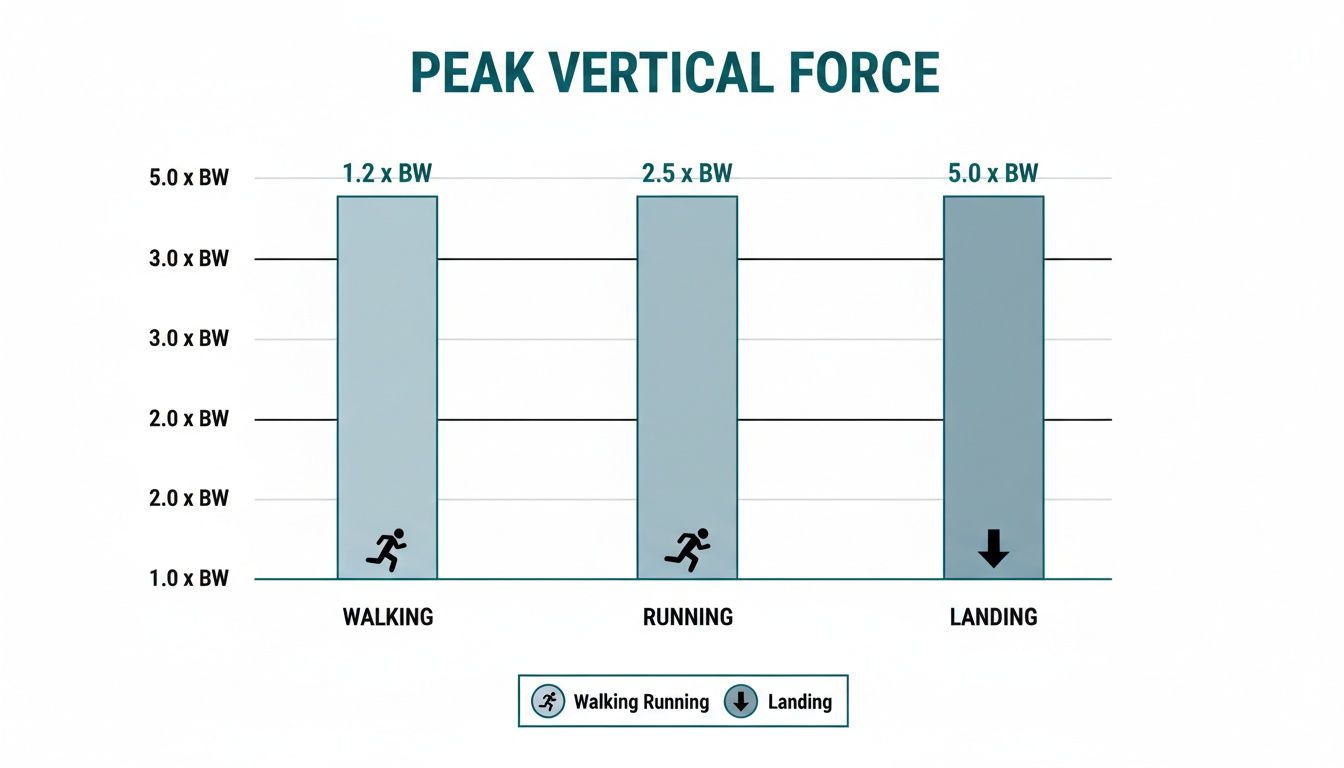

The peak vertical ground reaction forces (vGRF) we encounter daily are a great example. Simple walking can generate forces around 1.1 to 1.5 times body weight (BW). Increasing the pace to a run elevates this number to approximately 2.0 to 3.0 times BW (1).

High-impact activities, such as landing from a jump, can cause these forces to exceed 3.0 times BW (1). This highlights the incredible stress our musculoskeletal system is designed to handle. For a deeper dive into the science, you can read the full research on ground reaction forces.

Peak force provides an objective number that quantifies an individual's capacity for maximal effort. It removes the guesswork from assessing explosive strength, offering a clear benchmark for both rehabilitation progress and athletic development.

This measurement is a cornerstone in physiotherapy and performance training. Whether we're tracking recovery after an ACL injury or helping an athlete jump higher, understanding peak force allows for smarter, data-driven decisions that ultimately protect and enhance the human body.

The Tools Used to Measure Peak Force

To truly understand peak force, we must move beyond theory and capture objective data. This requires specialized technology that can translate a split-second muscular effort into quantifiable numbers.

In clinical and performance settings, the two main instruments for this task are force plates and dynamometers. While they both measure force, they do so in distinct ways, providing complementary views of an individual's physical capacity.

Getting the Full Story with Force Plates

A force plate can be thought of as a highly sensitive scale that captures the forces behind dynamic movements. When an athlete jumps on one, it doesn't just measure their weight; it records the entire force profile of that jump—from the initial dip and explosive push-off to the impact of the landing.

This provides a continuous stream of data, painting a complete picture of how force is produced and absorbed throughout a complex, full-body action. If you're curious to learn more about the mechanics, we cover it all in our guide to force platforms in biomechanics.

Isolating Strength with Dynamometers

A dynamometer, in contrast, is more like a precise gauge for a specific muscle or muscle group. These are often handheld devices used to measure isometric strength—the maximum force someone can produce without movement, such as pushing against an immovable object.

A common example is a physiotherapist using a dynamometer to test a patient's quadriceps strength after knee surgery. This provides a clear, objective number to track recovery and ensure strength symmetry between limbs.

The Force-Time Curve: Visualizing Strength

Whether the data comes from a force plate or a dynamometer, it is often visualized on a force-time curve. This graph plots force (y-axis) against time (x-axis). It shows exactly how quickly an individual can generate force, where they hit their maximum output, and how that force changes over the duration of the effort.

Peak force is the highest point on this curve. However, the shape of the curve itself tells a much richer story, revealing an individual's strategy for generating power and offering insights that a single number cannot provide.

Consider how dramatically peak vertical forces change between everyday activities. The chart below shows these forces as a multiple of body weight (BW).

It’s easy to see the significant jump in ground reaction forces as we move from walking to running, and finally to the high-impact demands of landing.

The Right Tool for the Job

To obtain accurate and meaningful peak force measurements, practitioners rely on these standard tools:

- Force Plates: The primary choice for analyzing complex, full-body movements. They capture vertical, horizontal, and lateral forces, making them ideal for assessing jump performance, landing mechanics, and balance.

- Dynamometers: These handheld or mounted devices are invaluable for isolating specific muscle groups. They are a staple in clinical settings for pinpointing strength imbalances, tracking rehabilitation progress, and making data-driven return-to-play decisions.

By using these instruments, practitioners move beyond subjective assessment. They are empowered to quantify strength, identify deficits, and build targeted training or rehabilitation programs based on precise, repeatable data.

What Your Peak Force Numbers Actually Mean

Obtaining a number from a dynamometer or force plate is just the first step. The real skill lies in interpreting the story that number tells. A raw peak force value, measured in Newtons (N), provides a snapshot of absolute strength, but it can be misleading without context.

For example, a 100 kg (220-pound) lineman will almost always produce a higher raw peak force than a 68 kg (150-pound) gymnast. But does that automatically make him stronger on a relative basis? Not necessarily. To make a fair comparison, we need to normalize the data.

Creating a Level Playing Field

This is where normalization is essential. By taking the raw peak force (in Newtons) and dividing it by the individual's body mass (in kilograms), we get a relative value expressed in Newtons per kilogram (N/kg). This shifts the focus from brute strength to efficiency.

This relative number provides a clearer picture of an individual's pound-for-pound strength. It helps us answer the more important question: who is more powerful relative to their own body weight? This is a critical distinction in both rehabilitation and performance settings.

Normalizing peak force to body weight transforms a simple number into a powerful comparative metric. It allows clinicians and coaches to benchmark an individual's progress against themselves over time and compare their output to peers in a scientifically valid way.

Peak Force Is Not the Whole Story

While peak force is a cornerstone metric, it’s only one component in the complex narrative of human movement. An athlete might be incredibly strong and able to produce a high peak force, but if they generate that force too slowly, it may have limited transfer to explosive sports.

This is why we must look at other metrics to build a complete profile of an athlete’s abilities.

Comparing Key Force Metrics

To truly understand an athlete's functional capabilities, we must look beyond just peak force. The table below breaks down key metrics and highlights how each contributes to the performance story.

| Metric | What It Measures | Clinical/Sporting Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Force | The absolute maximum force produced during a specific movement. | Represents an individual's maximum strength potential. Essential for assessing overall strength and setting a baseline. |

| Rate of Force Development (RFD) | How quickly an individual can reach peak force. | Measures explosive power. Critical for sports requiring rapid movements like sprinting, jumping, and changing direction. |

| Impulse | The total force applied over a period of time. | Represents the overall effect of a force (Force x Time). Key for understanding the total effort in actions like a jump take-off. |

Distinguishing between these metrics is vital. An athlete with a high peak force but a low RFD might need training focused on speed and explosiveness. Conversely, an athlete with a high RFD but lower peak force may benefit from a foundational strength program. By analyzing these numbers together, practitioners can design highly specific and effective interventions.

How Peak Force Guides Rehabilitation and Prevents Injury

In physiotherapy, peak force data serves as an objective lens. It cuts through the ambiguity of subjective feelings like "better" or "stronger" and provides quantifiable data to drive clinical decisions. This is about building safe, effective rehabilitation plans grounded in evidence.

By measuring an individual's peak force at the start of a program, we establish a clear baseline of their strength. This becomes the benchmark against which all future progress is measured, making it easier to see if an intervention is working and allowing for precise, informed adjustments.

A Clear Milestone for ACL Recovery

A prime example of peak force's utility is in post-operative ACL rehabilitation. The primary goal is to restore strength and function, but determining when an athlete is truly ready for the demands of their sport has often been a subjective call.

Peak force testing provides a definitive measure. We can assess the maximum voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) of the quadriceps on both the surgical and non-surgical leg. From there, we calculate a limb symmetry index (LSI)—a percentage comparing the two.

An LSI of 90% or greater is a widely accepted, evidence-based criterion for readiness to return to sport (2). It indicates that the recovering limb has regained sufficient strength to begin a safe, progressive re-integration into sport-specific activities.

This data-driven checkpoint reduces guesswork, may help minimize the risk of re-injury, and gives both the clinician and the athlete confidence in the return-to-play decision. Our detailed guide on how to use a dynamometer walks through the practical steps for capturing this crucial data.

Managing Load in Tendinopathies

Peak force is equally critical when managing tendinopathies, such as those affecting the patellar or Achilles tendon. These injuries are notoriously sensitive to load. Too little, and the tendon won't adapt and strengthen. Too much, and you risk a painful flare-up that sets recovery back.

Here, peak force measurements allow us to carefully monitor and manage the load being placed on the healing tissue during specific exercises. For instance, by measuring the forces generated during a calf raise or a squat, we can ensure the exercise intensity stays within a therapeutic window. This facilitates the controlled, mechanical loading needed to stimulate tissue repair without overloading it. When combined with other therapies, such as understanding how sports massage can alleviate chronic pain and muscle tightness, this methodical approach ensures rehabilitation progresses safely, building a more robust and resilient tendon.

Using Peak Force to Unlock Athletic Potential

Beyond rehabilitation, peak force measurement is a powerful tool for developing athletes. In strength and conditioning, objective data helps coaches move beyond visual assessment and fine-tune training with scientific precision. It’s about understanding an athlete's unique strength profile to unlock their true capabilities.

This shift from rehabilitation to performance involves using targeted tests to quantify the specific types of strength that are most relevant for a given sport. Two standard tests, in particular, provide complementary and crucial insights.

Quantifying Explosive and Maximal Strength

Coaches constantly seek to answer two fundamental questions: "How explosive is my athlete?" and "What's their absolute strength ceiling?" Different tests measure peak force in different ways to provide these answers.

-

The Countermovement Jump (CMJ): This dynamic test, performed on a force plate, is an excellent measure of lower-body explosive power. By analyzing the peak force an athlete generates during the upward propulsion phase, we can directly quantify their ability to produce force rapidly.

-

The Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull (IMTP): This test measures raw, maximal strength potential in a controlled, static position. The athlete pulls as hard as possible on an immovable bar, allowing for the measurement of their absolute peak force without the variables of movement. The IMTP provides a reliable indicator of their overall strength ceiling (3).

Together, these tests can create a detailed blueprint of an athlete's strength qualities.

Peak force data from tests like the CMJ and IMTP gives coaches a roadmap. It helps identify whether an athlete needs to improve their overall strength, or if they need to focus on applying their existing strength more explosively.

Translating Peak Force to On-Field Performance

The insights from these measurements translate directly into tangible performance gains. An increase in peak force during a CMJ isn't just a number on a screen—it's the foundation for a higher vertical leap, a more powerful first step, and a faster sprint.

For example, a 10% increase in an athlete's peak force could be the difference between winning a header in soccer or clearing a hurdle on the track. This is the practical application of peak force assessment in sports performance.

Ultimately, by understanding and training to improve this key metric, coaches can pinpoint and develop the specific strength qualities an athlete needs. This allows for smarter, more individualized programs that create more powerful, resilient, and effective athletes.

Common Mistakes and Best Practices in Measurement

Reliable data is the bedrock of any effective rehabilitation or training program. When measuring peak force, a standardized, repeatable process is necessary to ensure the numbers collected are accurate and clinically meaningful. Even with the best equipment, simple mistakes can compromise results.

Simply put, consistency is paramount. Without a strict protocol, you cannot make valid comparisons from one session to the next. This can lead to misinterpreting progress or, worse, making poor clinical decisions based on flawed data. The goal is to control every possible variable so that the only thing changing is the individual's actual force output.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

A few common errors can compromise the quality of peak force data. Awareness is the first step toward cleaner, more trustworthy measurements.

- Inconsistent Instructions: Using different verbal cues or varying the level of encouragement between tests can alter a person's effort and their results.

- Incorrect Equipment Setup: Improper dynamometer positioning or inconsistent joint angles can target different muscles or place the individual at a mechanical disadvantage, skewing the data.

- Testing While Fatigued: Attempting to get a maximal strength reading after a strenuous workout or when an individual is already tired will likely yield inaccurate data. It will not capture their true peak force potential.

A significant mistake is looking at a peak force number in a vacuum. A single data point has limited value. Its true utility emerges when contextualized with the individual's history, their movement quality, and the specifics of the testing protocol.

Best Practices for Reliable Data

To ensure your data is telling an accurate story, integrate these best practices into your testing protocol.

- Standardize Your Cues: Create a script for verbal instructions and adhere to it. Simple cues like, "Push as hard as you can for three seconds… 3, 2, 1, relax" create the necessary consistency. Research has shown that strong verbal encouragement can significantly boost maximal force output, making it critical to apply it consistently (4).

- Perform Multiple Trials: A single effort rarely represents a true maximum. It is standard practice to perform at least three trials and use the highest value. This simple step helps account for any learning effect and ensures you capture a genuine peak effort.

- Document Everything: This is non-negotiable. Record the testing position, the exact joint angles, and any relevant patient feedback. This detailed context is as crucial as the number itself and is the only way to ensure the test can be replicated precisely in the future.

Your Top Questions About Peak Force, Answered

As we conclude this overview of force measurement, let's address a few common questions from clinicians and coaches.

Is a Higher Peak Force Always Better?

Not necessarily. While high peak force is often a sign of great strength, the optimal level is context-specific.

For example, during a landing task, an excessively high peak ground reaction force can be a red flag for poor shock absorption strategies, potentially increasing stress on joints and elevating injury risk (1). The goal is often not just to maximize force, but to generate and absorb force in a controlled and efficient manner appropriate for the task.

How Is Peak Force Different From Strength?

This is an excellent question. Peak force is a specific data point—the single highest point of force produced during a movement. "Strength," on the other hand, is a broader, more general term for the body's ability to produce force.

Peak force is a critical component of strength, especially explosive strength. However, the complete picture of "strength" also includes factors like how quickly force is generated (Rate of Force Development) and how long it can be sustained. You can think of peak force as one of the most important metrics that helps us quantify the overall quality we call strength.

Can I Measure Peak Force Without Expensive Equipment?

To obtain a true, accurate measurement of peak force in Newtons, you do need specialized tools like a digital dynamometer or force plates.

However, this does not mean progress cannot be tracked without them. You can use "proxy" measurements. For example, consistently tracking an athlete's maximum vertical jump height is a practical, indirect way to monitor improvements in lower body power. While it is not a direct measurement in Newtons, a higher jump height is strongly correlated with an increased ability to generate force quickly and powerfully.

References

- Giandolini M, et al. The use of minimalist shoes to mitigate running-related impact loading: mechanistic differences and gaps in the literature. J Biomech. 2017;55:1-12.

- Grindem H, et al. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804-808.

- De Witt JK, et al. The isometric mid-thigh pull: A review of its reliability, validity, and applications in sport. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(11):3243-3262.

- Argus CK, et al. The effects of verbal encouragement on maximal jump-and-reach and grip strength performance in college-aged men. J Strength Cond Res. 2011;25(10):2864-2868.

Ready to stop guessing and start measuring? The Meloq ecosystem of digital dynamometers, force plates, and goniometers is designed to give you the objective data you need to make smarter, evidence-based decisions for your clients and athletes.

Explore the tools that are setting a new standard in rehabilitation and performance at Meloq.