A Guide to Velocity Based Training for Clinicians and Coaches

Team Meloq

Author

Velocity based training (VBT) represents a shift in focus in strength and conditioning, moving from primarily asking how much weight is on the bar to also asking how fast that weight is moving. This approach provides objective, real-time data on an athlete’s effort and physiological readiness, allowing for precise adjustments that traditional percentage-based programs often cannot accommodate.

What Is Velocity Based Training

For decades, strength training has often been analogous to judging a car's performance based solely on its cargo capacity while ignoring its acceleration. The obsession with the load on the bar has been a primary focus. Velocity Based Training (VBT) offers a more dynamic and data-informed approach to developing strength and power.

At its core, VBT is a method of autoregulating resistance training by measuring the speed of movement during an exercise. Instead of programming exclusively from a percentage of an athlete's one-repetition maximum (1RM)—a value that can fluctuate daily—VBT uses movement velocity to guide the training session. This provides immediate, objective feedback on an athlete's true effort, fatigue levels, and readiness to perform on any given day.

This data-driven method is a significant evolution from conventional percentage-based training. An athlete's ability to lift 85% of their 1RM can feel vastly different depending on factors like sleep quality, nutritional status, or external life stressors. VBT acknowledges this daily variability and provides a framework to adjust for it.

VBT vs Traditional Percentage-Based Training

To fully appreciate the distinction, it is helpful to compare the two approaches. Traditional training is often prescriptive and fixed, whereas VBT is responsive and fluid.

| Metric | Traditional %-Based Training | Velocity Based Training (VBT) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Driver | Prescribed percentage of a 1-Rep Max (1RM). | Real-time movement velocity of each repetition. |

| Daily Adjustment | Limited. The plan is fixed and does not readily account for daily readiness. | High. Adjusts load or repetitions based on velocity to match daily readiness. |

| Feedback | Subjective ("How did that feel?"). | Objective (e.g., meters per second). |

| Training Intent | Assumed. The prescribed load is intended to elicit a specific stimulus. | Confirmed. Ensures the athlete moves at the required speed for the desired adaptation. |

| Fatigue Management | Reactive. Often based on accumulated fatigue or subjective reports. | Proactive. Uses velocity drop-offs to terminate a set before technique degrades. |

This comparison highlights that VBT is not simply an alternative method; it represents a fundamental change in how training is monitored and adapted in real-time.

A More Precise Way to Train

With VBT, coaches and clinicians can ensure that each repetition is performed with the specific intent needed to drive a desired physiological adaptation. Different training goals are intrinsically linked to different movement velocities.

- High-velocity movements (e.g., >1.0 m/s) with lighter loads are ideal for developing explosive power and speed-strength.

- Lower-velocity movements (e.g., <0.5 m/s) with heavier loads are necessary for stimulating maximal strength gains.

By targeting specific velocity zones, practitioners can move beyond estimating whether prescribed percentages are achieving the intended goal. Real-time data provides confirmation. You can learn more about the technical aspects of this process in our guide on how to measure velocity.

Backed by Scientific Evidence

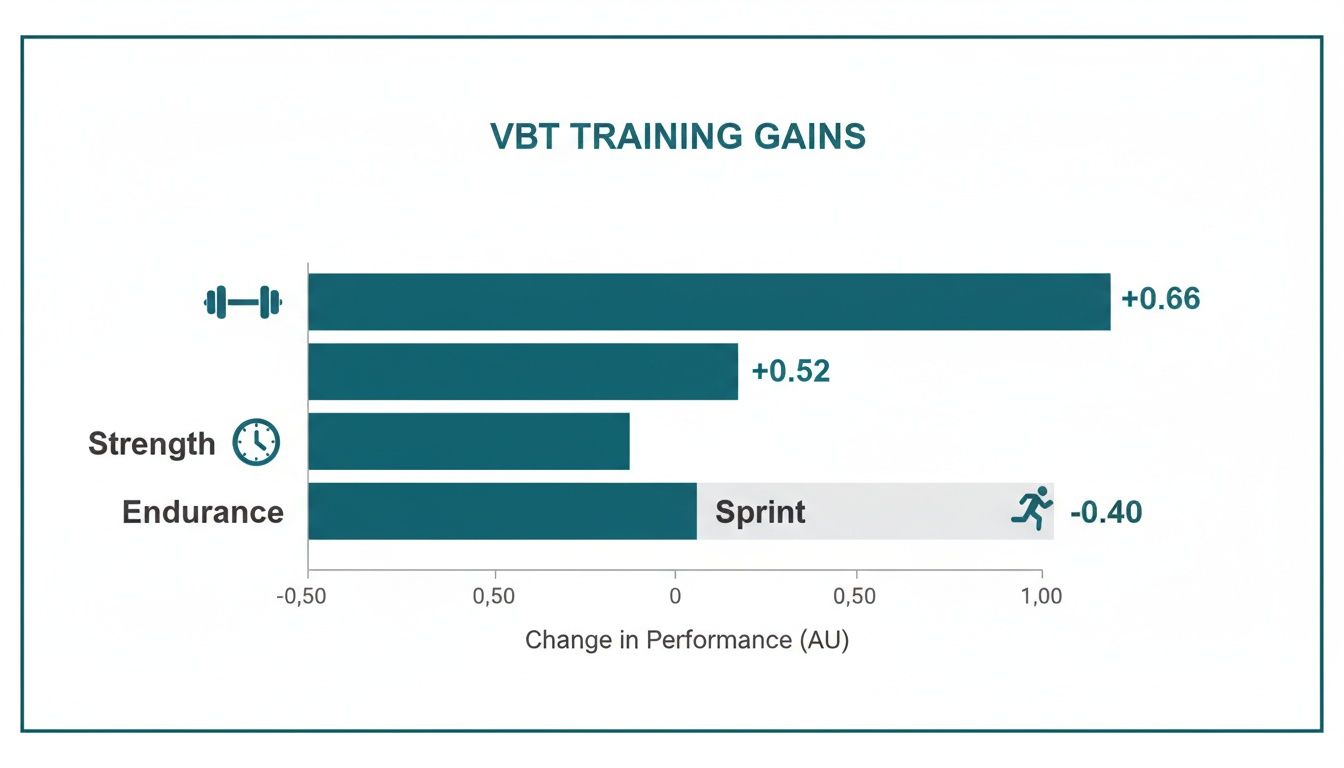

VBT is an approach grounded in a growing body of scientific research. A 2022 meta-analysis highlighted its effectiveness, concluding that VBT programs often outperform traditional percentage-based methods for certain performance outcomes (1).

The study reported notable improvements, with a standardized mean difference (SMD) of 0.66 for maximum strength, 0.52 for strength endurance, and a -0.40 reduction in sprint time (1). For a historical perspective on the researchers who pioneered this work, this detailed article on SimpliFaster provides an excellent overview.

By focusing on the quality of movement—specifically, its speed—VBT provides a powerful tool for optimizing performance, managing fatigue, and preventing overtraining in both clinical rehabilitation and elite sports settings. It transforms every training session into a diagnostic opportunity, allowing for truly individualized and responsive programming.

The Science of Why Velocity Matters

To understand what makes velocity based training effective, we must examine the underlying physiology. The process involves more than simply moving a load from one point to another; it relates to the high-speed communication between the central nervous system and the muscular system during every repetition.

At the heart of this is a fundamental principle of biomechanics: the Force-Velocity Relationship.

This principle describes a simple, inverse relationship: the more force required to move a load (e.g., a maximal squat), the slower the movement velocity will be. Conversely, to move a light load at maximum speed, significantly less force is generated relative to one's maximum capacity. The difference can be likened to pushing a stalled car (high force, low velocity) versus throwing a baseball (low force, high velocity).

Every training adaptation, from maximal strength to explosive power, corresponds to a specific point on this curve. While traditional percentage-based training provides a general map to target these qualities, VBT acts more like a GPS, allowing for precise targeting.

The Neuromuscular Connection

Why is movement speed so critical? Lifting with maximal intent—attempting to accelerate the load as rapidly as possible, regardless of its weight—sends an enhanced neural signal from the brain to the muscles. This is not just a matter of effort; it is a mechanism for improving neuromuscular efficiency and power.

This powerful neural signal increases motor unit recruitment. The nervous system not only recruits more muscle fibers but also increases the rate at which they are activated. This improved neural drive is a key factor in enhancing the rate of force development (RFD)—a term describing how quickly an athlete can generate force.

For those interested in exploring this topic further, our article on the force and velocity relationship offers more detail. A high RFD is crucial for nearly all athletic actions, from a sprinter's start to a basketball player's jump.

Training with velocity as a key metric is, in essence, skill practice for the nervous system. A pitcher does not develop a 95-mph fastball by only lifting heavy weights; they must practice the specific skill of throwing fast. VBT applies this concept to resistance training, teaching the neuromuscular system to be more explosive.

From Theory to Tangible Gains

This scientific theory translates directly to measurable performance improvements. A growing body of research has demonstrated that focusing on velocity can yield superior results compared to traditional methods alone.

The chart below, based on data from a major meta-analysis, illustrates how VBT can positively influence strength and endurance while also enhancing speed (1).

This evidence suggests VBT is a versatile tool applicable to a wide range of athletes, capable of developing well-rounded athleticism by targeting specific physical qualities with high precision.

Why Intent Is Everything

The scientific foundation of VBT rests on one non-negotiable principle: maximal intent. The athlete must attempt to move every repetition as fast as possible for that given load. This ensures that the velocity data is a true and accurate reflection of their neuromuscular capacity at that specific moment.

Without consistent, maximal intent, velocity data becomes unreliable. VBT is effective because it measures the output of a maximal effort, providing a clear window into the athlete's true performance state.

This focus on intent can be a powerful coaching tool. It reframes the athlete's goal from simply completing repetitions to executing each one with purpose and quality. By measuring what truly matters—the speed of the movement—we ensure the training stimulus aligns with the prescription, paving the way for better, more efficient results.

How to Use Velocity Zones in Your Practice

This is where the science of the force-velocity curve becomes highly practical. We can translate theory into a daily training plan using velocity zones—specific speed ranges (in meters per second) that correspond with distinct training goals.

Instead of only instructing an athlete to lift a certain percentage of their 1RM, you provide a velocity target. This shift helps ensure they receive the intended neuromuscular stimulus in every session.

This approach makes training highly responsive. If an athlete presents in a well-rested state, they may be able to move a heavier load than planned while staying within the target velocity zone. Conversely, if they are fatigued, the load can be reduced to maintain the correct speed, thereby preserving the quality of the training stimulus.

Understanding the Key Velocity Zones

Pioneering work by researchers like Bryan Mann has provided a clear framework for these zones (2). Each zone is linked to a primary physical adaptation, allowing coaches and clinicians to program with a high degree of precision.

Most frameworks categorize training into key qualities based on the average concentric velocity. These range from absolute strength, which involves moving very heavy loads slowly, to speed-strength, which focuses on accelerating lighter loads as rapidly as possible.

For example, to develop explosive power, an athlete might work within a velocity zone of 0.75-1.0 m/s. If the goal is to build maximal strength for a deadlift, the target velocity would be much lower, likely below 0.5 m/s.

A well-known model outlines five core training ranges. You can find a practical breakdown of these concepts at Bryan Mann's velocity zones on VBTCoach.com, which provides a useful map for structuring workouts.

From Theory to Daily Autoregulation

The practical power of velocity zones lies in autoregulation—the ability to adjust training in real-time based on an athlete's actual performance. This can remove much of the guesswork inherent in rigid, percentage-based programs.

Imagine your goal for an athlete's squat session is to develop power, targeting a velocity of 0.8 m/s. The plan calls for 102 kg (225 lbs), but on their first set, they only achieve 0.65 m/s. This is an immediate, objective indicator that they may be too fatigued for that load today.

With VBT, the adjustment is simple and data-driven. Instead of forcing them to complete subpar repetitions, you reduce the load on the bar until they can consistently achieve the target 0.8 m/s velocity. This ensures the session still accomplishes its intended purpose without excessively taxing an already-fatigued system.

This principle also applies when an athlete is performing better than expected. If they are exceeding the target velocity with the prescribed weight, it is a clear signal that they are ready for a greater challenge. You can confidently increase the load, knowing the stimulus remains perfectly aligned with their goals.

Practical Application of Training Zones

Mapping velocity zones to specific training goals and their corresponding 1RM percentages is how you implement this system. While the following values are guidelines and can vary between individuals and exercises, they provide a solid starting point.

Selecting exercises that are appropriate for the target velocity is a key part of this process. For a deeper look into movement selection, our guide on dynamic strength exercises provides context for applying these principles.

Practical Guide to VBT Zones and Training Goals

This table connects velocity, the targeted training quality, the expected adaptation, and the typical corresponding 1RM percentage range.

| Training Quality | Mean Velocity Range (m/s) | Primary Adaptation | Typical % of 1RM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute Strength | < 0.5 m/s | Maximal force production, neural drive | 85-100% |

| Strength-Speed | 0.5 - 0.75 m/s | Moving heavy loads quickly | 60-85% |

| Speed-Strength | 0.75 - 1.0 m/s | Moving moderate loads with high velocity | 45-60% |

| Starting Strength | 1.0 - 1.3 m/s | Overcoming inertia, rate of force development | 30-45% |

| Absolute Speed | > 1.3 m/s | Maximal movement velocity with light loads | < 30% |

Ultimately, using velocity zones transforms training from a rigid prescription into a dynamic process guided by the athlete's daily readiness. It is about ensuring every session is optimized to deliver the right stimulus at the right time.

Key VBT Metrics Beyond Mean Velocity

While mean velocity is the cornerstone of a VBT program, deeper insights can be gained by analyzing additional metrics. Moving beyond this single number allows for more precise fatigue management, a specific focus on explosiveness, and accurate strength monitoring.

Think of mean velocity as the average speed of a car on a long trip—a useful metric, but it doesn't reveal how quickly you accelerated from a stop or if the engine struggled on a steep incline. To get the complete picture, more detailed data is needed.

Managing Fatigue with Velocity Loss

One of the most powerful applications of VBT is tracking velocity loss. This is the percentage decrease in speed from the fastest repetition to the slowest repetition within a single set. It serves as an objective, real-time measure of neuromuscular fatigue.

As a set progresses, repetitions inevitably slow down due to fatigue. By setting a "velocity stop-loss," you can terminate the set at the precise moment the desired training stimulus has been achieved, before excessive fatigue compromises technique and hinders recovery.

For example, a coach might set a 20% velocity loss threshold for a set of squats. If the athlete’s first and fastest rep is 0.75 m/s, the set concludes as soon as a repetition falls below 0.60 m/s (a 20% drop). In this scenario, the prescribed rep count becomes secondary. This method autoregulates training volume based on the athlete's actual daily performance, prioritizing quality over quantity.

Peak Velocity for Explosive Movements

Mean velocity is an excellent metric for traditional strength exercises like the squat and bench press. However, for ballistic movements, peak velocity is often more informative. Peak velocity captures the single fastest moment during the concentric phase of an exercise.

This is particularly critical for movements where maximal acceleration is the goal, such as:

- Olympic Lifts: It isolates the explosive hip and knee extension during a clean or snatch.

- Jumps: It measures the highest velocity achieved at takeoff.

- Throws: It quantifies the release velocity of an implement like a medicine ball.

For these explosive actions, average speed may not capture the full picture. Peak velocity provides a clear window into an athlete's raw explosive power and their ability to generate force rapidly. To better understand this concept, you can review our article on the rate of force development.

The Load-Velocity Profile: Your Performance Fingerprint

Perhaps the most valuable tool in the VBT toolkit is the load-velocity profile. This is an individualized map of an athlete's unique relationship between the load lifted and the velocity at which they can move it.

Creating a profile is straightforward. An athlete is tested on a specific lift (e.g., back squat) using several distinct loads, from light to heavy, with maximal intent on every repetition. Plotting these data points reveals a predictable, nearly linear relationship: as load increases, velocity decreases.

This profile is a powerful tool because it allows you to accurately estimate an athlete's daily 1-Repetition Maximum (1RM) without requiring a maximal, fatiguing, and potentially risky test.

By measuring the velocity of a few warm-up sets, you can use the profile to extrapolate their true 1RM for that specific day. This is an invaluable asset for safely tracking progress in rehabilitation settings or managing athlete fatigue during a long competitive season. It elevates VBT from a simple monitoring tool to a robust predictive and programming instrument.

Putting VBT Into Practice in Clinical and Performance Settings

This is where theory is translated into practice. The application of velocity based training can transform how athletes and patients are managed by introducing objective data into decisions that were once primarily based on observation and subjective feedback.

The process begins with selecting appropriate core exercises—typically large, multi-joint movements like squats, deadlifts, and presses—and establishing an athlete’s baseline by creating their individual load-velocity profile for each key lift. This profile serves as their unique performance fingerprint.

This profile is the foundation of an effective VBT program, as it reveals how an individual responds to different loads and enables truly personalized programming.

VBT for Strength and Conditioning Coaches

For strength coaches, the primary benefit of velocity based training is daily autoregulation. An athlete's readiness can fluctuate significantly due to factors like sleep, nutrition, and academic or life stress. A rigid, percentage-based program cannot easily adapt to this variability.

VBT provides an immediate solution. By focusing on a target velocity for the day's primary exercise, the load can be adjusted—up or down—to match the athlete's capacity on that specific day. If the goal is strength-speed with a target of 0.65 m/s, the weight is simply modified until that velocity is consistently achieved. The desired training stimulus is met every time.

Furthermore, providing real-time velocity feedback can be a powerful motivator. When athletes see their velocity displayed after each repetition, it can create a competitive and engaging environment. They are no longer just moving a weight; they are chasing a specific number, which can sharpen focus and increase output.

The concept of augmented feedback is supported by scientific evidence. Research indicates that providing immediate velocity data can be superior for improving sprint and jump performance compared to training without it, as it fosters a more intentional and productive training session (1).

VBT in the Physical Therapy Clinic

In a clinical or rehabilitation setting, VBT is a valuable tool for guiding return-to-play protocols and monitoring neuromuscular recovery. Following an injury, it provides an objective method for tracking an athlete's function and readiness to progress, moving beyond reliance on subjective feedback alone.

For example, a physical therapist can use VBT to quantify asymmetries between an injured and uninjured limb. By measuring velocity and power output during a bilateral exercise like a squat or a unilateral movement like a single-leg press, the clinician obtains clear, numerical data on force production deficits. A significant difference in velocity at the same relative load indicates that the neuromuscular system on the injured side may not have fully recovered.

This data is invaluable for making safe and effective programming decisions. As the velocity gap between limbs narrows over time, it provides a data-backed rationale for advancing the patient to more demanding activities. This objective tracking helps ensure that load is progressed appropriately, minimizing re-injury risk while building a solid foundation for a full return to sport.

The performance impact is well-documented. The same 2022 meta-analysis found that VBT led to significant improvements in key athletic markers, reporting a standardized mean difference of 0.53 for countermovement jump height and -0.40 for sprint time reduction (1). You can explore the full findings from this meta-analysis on VBT's impact on performance.

Common Questions About Velocity Based Training

Adopting a new training methodology naturally raises questions. As coaches and clinicians begin to explore the applications of VBT, several common queries tend to arise. Let's address them directly.

Do I Need Expensive Equipment to Start with Velocity Based Training?

No, not necessarily. While high-end linear position transducers were once the only option, the barrier to entry for VBT has lowered significantly. It is possible to begin exploring the core principles with more accessible tools.

Wearable sensors or even certain smartphone applications can serve as a starting point. They are often sufficient for learning the workflow, teaching athletes about lifting with intent, and becoming familiar with the data.

However, in clinical or high-performance environments where decisions carry significant weight, investing in a validated and reliable device is advisable. When making critical judgments about return-to-play or programming for an elite athlete, the data must be trustworthy. The precision of the tool should match the importance of the decisions being made with it.

Is VBT Only for Elite Athletes?

This is a common misconception. While VBT gained prominence in professional and collegiate sports, its principles are universal and valuable for a wide range of individuals. In fact, some of its most powerful applications are in rehabilitation.

For physical therapists, VBT provides an objective way to manage load and monitor neuromuscular recovery post-injury. Instead of simply progressing weight, exercise can be prescribed based on movement quality (velocity), ensuring patients are appropriately challenged without being pushed into a high-risk zone. The data offers clear benchmarks for progress.

For the general gym-goer, VBT can be highly motivating. It can "gamify" training by providing immediate feedback and clear targets for each set. More importantly, it reinforces a crucial principle of strength training: lifting with maximal intent. This concept is a fundamental driver of long-term strength and power development.

How Does VBT Account for Different Exercises and Individuals?

This is a core strength of VBT. The relationship between load and movement velocity is unique to each individual and to each specific exercise. VBT is not a one-size-fits-all program; it is inherently individualized.

Best practice involves creating a load-velocity profile for each individual on their primary lifts, such as the squat, bench press, or deadlift, rather than relying on generic charts. This profile acts as a personal performance fingerprint.

This individual profiling is what makes VBT so powerful. One person's 0.5 m/s squat velocity might correspond to 85% of their 1RM, while for another, it could be closer to 90%. By creating and referencing these individual profiles, training becomes truly customized and autoregulated based on that person's specific capabilities on any given day.

What Are the Main Limitations or Considerations of VBT?

While VBT is an excellent tool, its effective implementation requires thoughtful consideration. There is a learning curve for both the coach and the athlete. The practitioner must learn to interpret the data and make intelligent, real-time adjustments.

Simultaneously, athletes or patients must learn to perform every repetition with maximal voluntary intent. The entire methodology is predicated on measuring the output of an all-out effort. If intent is lacking, the data is not meaningful. This requires consistent coaching and reinforcement.

A few other points to keep in mind:

- Device Reliability: The accuracy of your measurement tool is paramount. Inaccurate data can lead to poor programming decisions, undermining the purpose of VBT.

- Exercise Selection: VBT is most effective for large, multi-joint barbell exercises with a consistent bar path. It is less useful for isolation movements or exercises with significant technical variability.

- Holistic Programming: VBT is a tool that fits within a well-designed program, not a replacement for one. Sound periodization, appropriate exercise selection, and a focus on overall recovery remain the cornerstones of effective training.

At Meloq, our mission is to equip professionals with the objective data they need to make better, more confident decisions. Our ecosystem of portable and accurate measurement tools, like the EasyForce dynamometer and EasyBase force plate, helps you quantify every aspect of performance and recovery. See how you can elevate your practice by visiting https://www.meloqdevices.com.

References

- Weakley, J., Mann, B., Banyard, H., McLaren, S., Scott, T., & Garcia-Ramos, A. (2021). Velocity-based training: From theory to application. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 43(2), 31-49.

- Mann, J. B., Ivey, P. A., & Sayers, S. P. (2015). Velocity-based training in football. Strength & Conditioning Journal, 37(6), 52-57.