A Clinician's Guide to the Functional Movement Screening Test

Team Meloq

Author

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) is not a tool for diagnosing an existing injury. Instead, it serves as a standardized method to evaluate fundamental movement patterns. Think of it as a quality control check for the body's basic movements, analogous to inspecting a car's chassis for integrity before installing a high-performance engine. A solid frame is necessary before adding power.

Why Quality of Movement Comes First

Attempting to build athletic performance on a foundation of dysfunctional movement is like constructing a race car on a crooked frame. Regardless of the engine's power, the misaligned chassis will compromise performance and eventually lead to a breakdown. This principle applies directly to the human body. The functional movement screening test provides a systematic way to assess the integrity of our movement patterns.

This approach is grounded in the concept of the kinetic chain, which views the body as a series of interconnected segments. A minor limitation in one link, such as poor ankle mobility, can create significant issues elsewhere, potentially affecting the knees or lower back. The FMS offers clinicians a standardized language to identify these asymmetries and limitations—factors that may hinder performance and potentially increase injury risk. A primary goal is to identify movement dysfunctions that could contribute to injuries, which is a key aspect of strategies to prevent sports injuries.

The Origins of the FMS

Developed by physical therapist Gray Cook and athletic trainer Lee Burton, the FMS was designed to bridge the gap between a standard pre-participation physical and specific physical performance testing. It establishes a baseline of movement quality, helping practitioners identify areas that require attention.

The FMS consists of seven tests that assess and score foundational movement patterns. At its core, it is a system designed to observe how well the body's segments coordinate during movement.

By screening these patterns, we can identify functional limitations and asymmetries. These are issues that can reduce the effects of functional training and physical conditioning and distort body awareness.

This screening method has become a widely used tool in physiotherapy and sports conditioning for several key reasons:

- It creates a baseline: It provides a clear snapshot of an individual's movement quality before they begin a training program.

- It identifies major limitations: The screen is effective at quickly flagging significant asymmetries or major restrictions in fundamental movements.

- It provides a common language: It gives therapists, trainers, and coaches a consistent framework for discussing and tracking movement over time.

Breaking Down the Seven Foundational Movement Tests

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) does not measure strength or speed. It is a movement quality assessment—a systematic method for observing how the body performs seven fundamental movement patterns. The screen is designed to reveal potential weak links in the kinetic chain before they become significant problems.

Each of the seven tests challenges mobility, stability, and motor control in different ways. The primary objective is to identify asymmetries—subtle or obvious differences between the left and right sides—and major limitations that might otherwise go unnoticed. Understanding these tests is the first step toward building a more robust and efficient movement foundation.

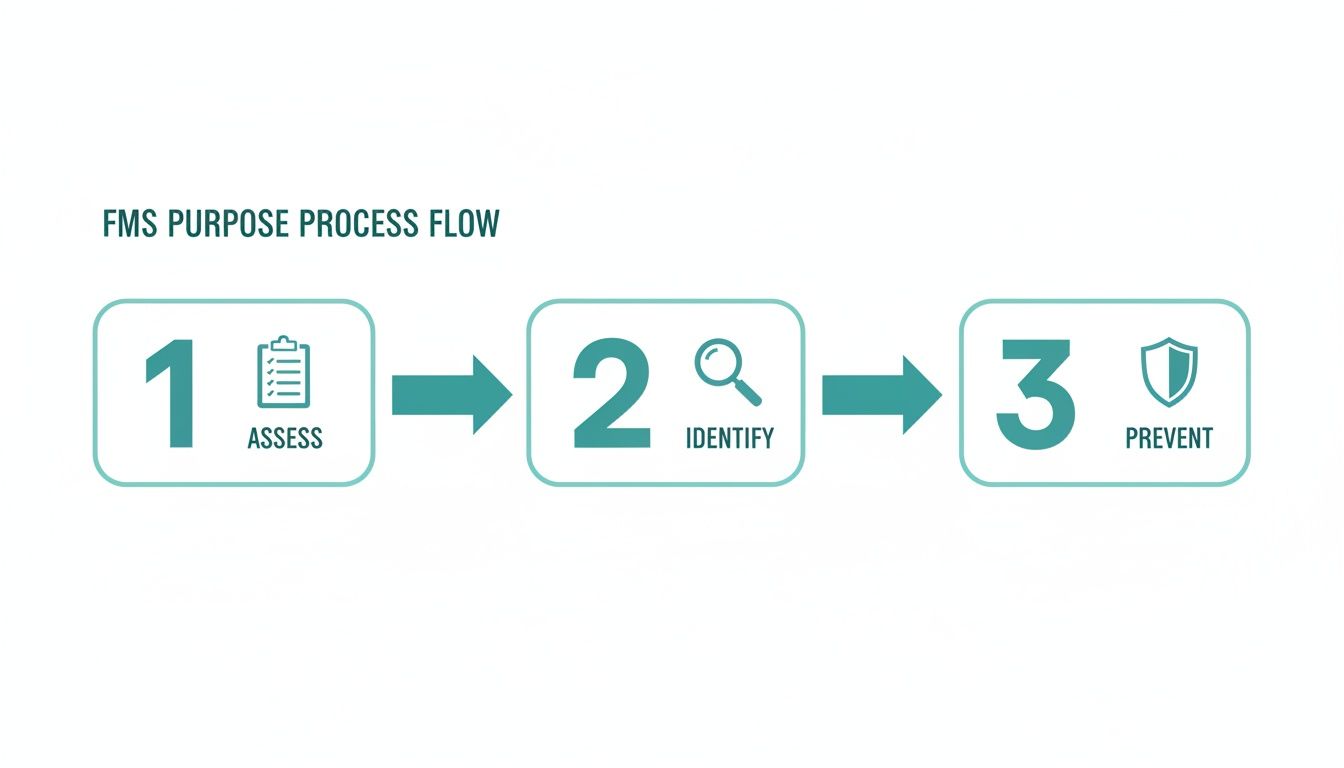

The core purpose is straightforward: assess movement, identify potential dysfunctions, and help guide corrective strategies.

It is critical to remember that screening is not diagnosing. It is a process of gathering information to inform better training and rehabilitation decisions. Let's explore each test and what it can reveal.

The Deep Squat

This is a comprehensive test of total-body mobility and motor control, requiring synchronized movement from the ankles, knees, hips, thoracic spine, and shoulders.

- Purpose: To assess bilateral, symmetrical mobility and stability of the hips, knees, and ankles.

- How it's done: Holding a dowel overhead, the individual squats as deeply as possible while keeping their heels on the ground, torso upright, and the dowel aligned over their feet.

- What it reveals: Limitations in this movement often suggest restrictions in ankle dorsiflexion, hip mobility, or thoracic spine extension. These limitations can force compensations throughout the kinetic chain. For example, if poor ankle mobility is suspected, one can learn how to measure ankle dorsiflexion to obtain a precise, objective measurement of that specific limitation.

The Hurdle Step

This test shifts the focus to single-leg stance, challenging balance, mobility, and stability during a dynamic movement.

- Purpose: To assess single-leg stability and hip mobility.

- How it's done: The individual steps over a hurdle (typically a string set at the height of their tibial tuberosity) without losing balance or deviating from an upright posture.

- What it reveals: Instability in the stance leg or a hip hike in the moving leg may indicate poor stability on the standing side or restricted mobility in the stepping hip. This can translate to inefficiency during sport-specific movements like sprinting or changing direction.

The In-Line Lunge

By narrowing the base of support, the in-line lunge significantly challenges stability in a split-stance position.

- Purpose: To evaluate hip and ankle mobility, stability, quadriceps flexibility, and torso control in an unstable position.

- How it's done: From a split stance with both feet on a line, the person lunges straight down while holding a dowel vertically along their spine.

- What it reveals: Difficulty performing this movement cleanly often points to instability in the trunk or hips. This is a critical pattern for athletes who need to transfer force from a stable base, such as throwers or racquet sport players.

The Shoulder Mobility Test

This screen assesses the complex relationship between the glenohumeral joint's range of motion and the stability of the scapula and thoracic spine.

- Purpose: To assess bilateral shoulder range of motion, combining internal rotation with adduction and external rotation with abduction.

- How it's done: In a standing position, one hand reaches over the shoulder while the other reaches up the back. The distance between the fists is measured.

- What it reveals: A significant difference in reach between sides is noteworthy, particularly for overhead athletes. Limited range of motion here may lead to compensatory movements, potentially overloading the shoulder joint or lower back.

The objective is not just to have an ample range of motion, but to possess symmetrical and controllable range. Asymmetry often hints at an underlying imbalance that may become problematic under load.

The Active Straight-Leg Raise

This test isolates the ability to move one leg into flexion while maintaining stability throughout the rest of the body.

- Purpose: To test active hamstring and calf flexibility while maintaining a stable pelvis and core.

- How it's done: Lying supine, the individual raises one leg as high as possible while keeping the other leg flat on the ground and both knees extended.

- What it reveals: A poor score may suggest limited hamstring flexibility or, commonly, insufficient pelvic control from the core musculature. For runners, this is highly relevant; a significant asymmetry in this pattern could disrupt stride mechanics and potentially increase the risk of muscle strains.

The Trunk Stability Push-Up

This is not a test of upper-body strength; it is a screen for core stability during a dynamic upper-body movement.

- Purpose: To assess core stability in the sagittal plane while the upper extremities are in motion.

- How it's done: The individual performs a push-up, moving their body as a single, solid unit without any sag in the lower back.

- What it reveals: A common compensation is a "cobra" push-up, where the hips sag and the lumbar spine hyperextends. This demonstrates an inability to transfer force through a stable core, which is a potential contributor to low back pain in athletes who generate rotational power.

The Rotary Stability Test

This test challenges the body's ability to coordinate movement between contralateral limbs while resisting rotation.

- Purpose: To assess multi-planar trunk stability and the neuromuscular coordination between the upper and lower body.

- How it's done: From a quadruped position, the individual simultaneously extends the opposite arm and leg, then brings the elbow and knee together under the body without losing balance.

- What it reveals: Difficulty with this test may indicate a weak link in the body's diagonal fascial "slings," which are essential for most athletic movements like throwing, swinging, and cutting.

How to Interpret FMS Scores for Clinical Application

After administering the functional movement screening test, the next step is to translate the scores into a meaningful plan. The true value of the FMS lies not in the final composite score, but in the detailed interpretation of each component to build a targeted and effective program.

It is easy to focus on the total score out of 21, but viewing the FMS as a simple pass/fail test overlooks its primary purpose. The screen should be considered a filter designed to highlight the most significant movement issues, guiding the practitioner on where to investigate further.

The Composite Score and the Threshold of 14

The number 14 is frequently mentioned in discussions about the FMS. Some research has suggested that a composite score below this threshold is associated with a higher risk of non-contact injury in certain athletic populations (1). However, this finding should be interpreted with caution. It is not a definitive predictor of future injury.

A score below 14 can be viewed as a signal that an individual's overall movement competency may be compromised. This suggests that it may be prudent to prioritize foundational movement patterns before progressing to high-intensity training. The score serves to initiate a conversation about movement quality, not to deliver a final judgment.

A low composite score does not predetermine that an athlete will sustain an injury. It indicates that their movement patterns exhibit inefficiencies that could, under certain conditions, contribute to a breakdown.

Why Zeros and Asymmetries Are the Priority

The most critical information from a functional movement screening test can be missed if one only focuses on the total score. The FMS scoring system is hierarchical, prioritizing pain and asymmetries above all else.

-

A Score of '0' for Pain: This is the most significant finding. If an individual reports pain during any of the seven movements, that specific test is immediately stopped and scored as a '0'. Pain supersedes all other scores. A '0' indicates the need for a referral to a qualified healthcare professional, such as a physical therapist, for a thorough clinical evaluation to determine the cause of the pain. Painful movement patterns should not be trained.

-

Asymmetry (Different Scores Side-to-Side): This is arguably the next most important finding. A discrepancy between the left and right sides on tests like the Hurdle Step, In-Line Lunge, or Shoulder Mobility is a key indicator. For instance, scoring a '2' on the right lunge but a '1' on the left reveals a functional imbalance. The body often compensates for a weak or restricted side, and over time, these compensations may lead to overuse injuries. Addressing asymmetries should be a top priority in any corrective strategy.

Only after addressing pain and asymmetry should the focus shift to bilateral limitations, such as when an individual scores a '1' on both sides of the Active Straight-Leg Raise.

Translating Scores into a Corrective Strategy

Interpreting FMS scores provides a logical roadmap for program design. The results create a priority list for intervention:

- Address the Zeros: Any score of '0' requires an immediate referral for clinical evaluation. Pain should not be "corrected" with exercise.

- Correct the Asymmetries: Focus on the side that scored lower. The goal is to improve the function of the weaker or more restricted side to match the other.

- Improve Bilateral Dysfunctions ('1s'): Once asymmetries are addressed, work on the dysfunctional patterns where the individual scored a '1' on both sides.

- Refine Competent Patterns ('2s'): Finally, movements that were scored as a '2' can be refined to improve quality and efficiency.

This systematic approach ensures that the most pressing issues are addressed first. It facilitates a transition from simply identifying potential risks to strategically building a more resilient and efficient mover. This process is analogous to how clinicians use what is normative data to compare an individual's results to a relevant population in other clinical contexts.

References

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

Examining the Scientific Evidence Behind the FMS

The utility of any screening tool in physiotherapy or sports performance depends on the scientific evidence supporting it. For the Functional Movement Screen, a substantial body of research exists, providing a clearer understanding of its strengths and limitations. Clinicians must be familiar with this evidence to apply the FMS responsibly.

The discussion begins with reliability—does the test consistently produce the same results? If two trained professionals screen the same athlete, their scores should be nearly identical if the FMS is reliable.

The research on this aspect is generally positive. Studies have consistently demonstrated good to excellent inter-rater reliability for the FMS when administered by trained individuals (1). This means that with proper training, clinicians can score the seven movements consistently, providing a stable baseline for tracking an individual's progress.

Validity and Injury Prediction

With reliability established, the focus shifts to more complex questions. Does the FMS measure what it purports to measure—fundamental movement quality? And can it predict who is likely to sustain an injury? This is where the scientific discussion becomes more nuanced.

Some early research suggested an association between lower FMS scores and a higher incidence of non-contact injuries. One widely cited meta-analysis reported that a composite score below 14 was associated with an increased injury risk in some athletic groups (2).

However, it is crucial to interpret this finding with caution. A low score is not a definitive prediction of injury; it is one factor among many. It flags potential movement dysfunctions that, when combined with other variables like training load, fatigue, and sport-specific demands, could increase an athlete's vulnerability.

The FMS is best utilized as a tool to identify movement 'red flags' rather than to predict an athlete's destiny. It provides valuable information about movement competency, which is one component of the much larger injury risk profile.

A Balanced View from the Evidence

More recent and comprehensive systematic reviews advocate for a more measured perspective on the FMS's predictive ability. These analyses conclude that while the FMS is a reliable screen for movement quality, its capacity to predict injury on its own is limited, especially in elite athlete populations (3).

This does not render the tool invalid; it clarifies its appropriate role. The evidence suggests that the FMS should not be the sole determinant for return-to-play decisions or injury forecasting. Its primary strength lies in identifying significant asymmetries and fundamental movement limitations that warrant further investigation.

For a deeper exploration of how movement analysis contributes to athletic performance, our article on the biomechanics of sport and exercise may be of interest.

Ultimately, the scientific evidence supports using the FMS to help answer a key question: "Does this individual possess the fundamental movement competency to safely handle the physical demands of their training or sport?" If the screen reveals poor patterns, the logical next step is not to cease activity, but to address those weak links with targeted corrective exercises before progressing to more intensive training.

References

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Lorenson CL, et al. The Functional Movement Screen: a reliability study. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2012;42(6):530-540.

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

- Moran RW, Schneiders AG, Mason J, Sullivan SJ. Do Functional Movement Screen composite scores predict subsequent injury? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(23):1661-1669.

Critiques, Limitations, and the Future of Movement Screening

No single tool is a panacea, and the functional movement screening test is no exception. While it offers a valuable snapshot of fundamental patterns, it is crucial to understand its limitations and the ongoing discussions within the clinical and research communities.

A critical perspective allows us to use the FMS not as an infallible diagnostic tool, but as the effective screening instrument it was designed to be.

One common critique concerns the general nature of the seven tests. The movement demands of an elite gymnast are vastly different from those of a marathon runner, leading some to argue that the screen lacks sport-specific context. While this is true, this critique somewhat misunderstands the screen's intent. The FMS was not designed to replicate specific athletic skills but to verify that the foundational "hardware" of movement is functioning correctly before layering on specialized "software."

Another point of debate is its predictive power for injury. As discussed, while some studies have associated low FMS scores with an increased risk of injury, a low score should not be interpreted as a definite prediction of a future event (1). It simply raises a flag indicating that further attention is warranted.

The key is to view the FMS as a screening tool, not a comprehensive diagnostic assessment. It is designed to help us ask better questions and guide further investigation, not to provide definitive answers.

The Technological Leap Forward

The future of movement screening is advancing with technology, aiming to move beyond subjective visual assessment toward objective, quantifiable data. This evolution is making movement analysis more precise, accessible, and scalable.

Integrating objective measurement tools is a key step. For example, instead of visually estimating a limitation in the Active Straight-Leg Raise, a clinician can use a digital goniometer like EasyAngle to obtain an exact angle of hip flexion. Similarly, asymmetries observed in the Hurdle Step can be precisely quantified using force plates like EasyBase to measure ground reaction forces and weight distribution. This technology enhances, rather than replaces, the FMS by adding a layer of objective data to the visual screen.

Traditional FMS vs Technology-Enhanced Screening

This table compares traditional FMS methods with a modern, data-driven approach.

| Feature | Traditional FMS | Technology-Enhanced FMS |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Qualitative, observational (e.g., "good," "poor") | Quantitative, objective (e.g., degrees, newtons) |

| Objectivity | Subject to rater experience and bias | High; consistent and repeatable data |

| Precision | Low; visual estimation lacks fine detail | High; detects subtle asymmetries and deficits |

| Baseline Tracking | General progress notes | Precise, data-driven progress tracking over time |

| Cost | Low initial cost (certification, kit) | Higher initial investment in hardware/software |

| Efficiency | Can be time-consuming; manual scoring | Faster data capture and automated reporting |

While the traditional FMS is accessible and provides a valuable starting point, augmenting it with technology offers a level of insight that the naked eye cannot match.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence

The next frontier is artificial intelligence. Manual assessments can present scalability challenges, as they can take 10-15 minutes per person and require trained experts. AI has the potential to address this. A 2023 study introduced a dataset designed to automate FMS assessments, achieving high accuracy in predicted scores using computer vision. This technology can analyze movement, score tests automatically, and reduce human subjectivity. You can learn more about these developments in the full research on automated FMS scoring.

AI-driven platforms could soon offer more equitable access to high-quality movement screening, minimizing bias and expanding its reach from elite sports to general fitness. The future is not about replacing the clinician's expertise but augmenting it with powerful, data-driven tools to make high-quality movement screening a universal standard.

References

- Moran RW, Schneiders AG, Mason J, Sullivan SJ. Do Functional Movement Screen composite scores predict subsequent injury? A systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(23):1661-1669.

Common Questions About the Functional Movement Screen

Even with a solid understanding of the tests and scoring, questions often arise when applying the FMS in practice. Here are some of the most common inquiries from clinicians and clients.

What Is a Good FMS Score for Athletes?

It is tempting to focus on achieving a perfect score of 21, but this is not the primary goal. While some research has identified a score of 14 or higher as a general benchmark for reduced injury risk, this should be treated as a guideline, not an absolute rule (1).

The most valuable insights are found in the details of the score. An athlete with a balanced score of 16 (all 2s with one 3 on each side) is likely in a better functional state than someone with a score of 17 that includes a significant asymmetry. The objective is balanced, pain-free movement, not simply a high total score.

How Often Should Someone Be Screened?

Movement quality is dynamic and can change with training loads, fatigue, and recovery. Therefore, the FMS should not be a one-time assessment. A strategic approach involves several key checkpoints:

- Pre-Season: To establish a clear baseline before intensive training begins.

- Mid-Season: To monitor how an athlete is adapting to training demands, especially if performance has plateaued or minor complaints have arisen.

- Post-Injury: As part of a return-to-play protocol to ensure fundamental movement patterns have been restored before a full return to sport.

Regular screening transforms the FMS from a static test into a dynamic monitoring tool, enabling more proactive training adjustments.

Can I Improve My FMS Score on My Own?

Yes, but improvement requires a targeted approach. The first step is to identify the specific "weak link" revealed by the screen. Is it a mobility restriction, a stability issue, or a motor control problem?

The most effective way to improve an FMS score is by addressing the specific limitations identified during the test. For instance, if the Deep Squat is limited by poor ankle mobility, simply practicing the squat won't fix the root cause. You must first improve ankle dorsiflexion.

This highlights a core principle: the test itself is not the corrective exercise. A low score on the Active Straight-Leg Raise, for example, signals a need to work on hamstring mobility and core stability. Merely repeating the leg raise without addressing the underlying limitation is unlikely to produce lasting change. This is where guidance from a qualified professional can be invaluable in designing an effective corrective program.

Is the Functional Movement Screen for Everyone?

The FMS was designed to assess fundamental movement patterns relevant to nearly everyone, from professional athletes to recreational fitness enthusiasts. It is an excellent starting point for anyone embarking on a new physical activity program.

However, context is critical. It is not a diagnostic tool for individuals currently experiencing pain. If an individual reports pain during any of the tests (resulting in a score of '0'), the screen should be stopped immediately. This is a clear indication that a full clinical evaluation by a physical therapist or other healthcare professional is the necessary next step. The FMS assesses movement competency, which requires a pain-free baseline.

References

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

At Meloq, we believe that objective data is the key to unlocking human potential. By replacing subjective guesswork with precise, repeatable measurements, our digital goniometers, dynamometers, and force plates empower clinicians to make more informed decisions, track progress accurately, and help clients achieve better outcomes. Discover how our tools can bring a new level of clarity and confidence to your practice at https://www.meloqdevices.com.