A Clinician's Guide to Functional Movement Screening

Team Meloq

Author

Functional movement screening is a standardized system for evaluating fundamental movement patterns. It's designed to identify significant limitations, asymmetries, and pain during these movements, providing a snapshot of an individual's movement quality. The primary goal is to identify potential "weak links" that could compromise performance or increase the risk of injury.

What's The Point Of a Movement Screen?

A functional movement screen serves as a baseline for movement quality. It is crucial to understand that it is not a diagnostic tool and is not designed to pinpoint a specific medical condition. Instead, it is a screening process that highlights areas of dysfunction.

A useful analogy is the "movement alphabet." Just as letters are the building blocks for words, fundamental movements like squatting, lunging, and reaching are the building blocks for all complex activities, from daily tasks to elite athletic performance.

If an individual cannot form certain letters clearly, their writing will be inefficient. The same principle applies to movement. If a person cannot perform these basic patterns correctly, their more complex actions in sports and daily life will likely be inefficient and compensated, potentially increasing risk. The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) provides a systematic way to check each of these foundational patterns for competence.

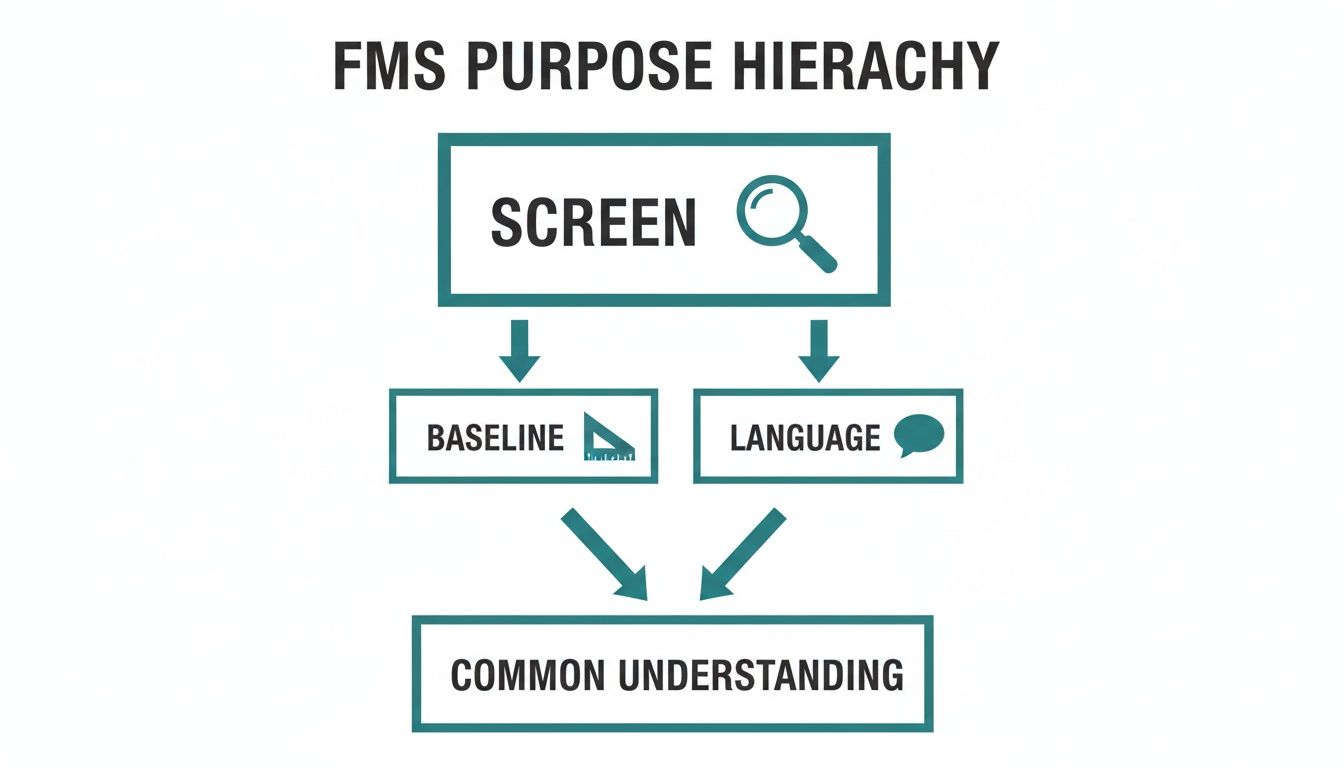

A Common Language for Movement

One of the most valuable contributions of the FMS is establishing a common language. When a physical therapist, a strength coach, and an athlete all use the FMS framework, they can communicate clearly about movement quality.

A "score of 1 on the in-line lunge" holds a specific, universal meaning for everyone involved. This ensures that corrective strategies are aligned and consistent, which is a significant advantage in any collaborative setting.

This shared understanding helps to:

- Establish a baseline: It captures an individual's movement competency at a specific point in time, which is essential for tracking progress.

- Identify major limitations: It quickly flags the most significant issues that need to be addressed first.

- Guide corrective strategies: The results point toward targeted mobility, stability, or motor control exercises.

Where Did The FMS Come From?

The FMS was developed out of a clinical need for a more reliable and systematic way to assess movement. Physical therapist Gray Cook and athletic trainer Dr. Lee Burton developed the Functional Movement Screen (FMS) in the late 1990s, finalizing the seven core tests in 1997.

Interestingly, the first peer-reviewed research study on the FMS was not published until a decade later in 2007. This period allowed the system years of real-world clinical observation and refinement before it underwent formal scientific validation.

Ultimately, the goal of functional movement screening is to improve the fundamental biomechanics of sport and exercise, ensuring athletes and patients have a solid foundation upon which to build strength, skill, and resilience.

Breaking Down The 7 FMS Tests and Scoring

The Functional Movement Screen is built around seven specific tests, each designed to challenge the body in a way that uncovers underlying limits in mobility, stability, and motor control. These are not random exercises; they are foundational patterns that serve as the building blocks for nearly all complex movements.

To use the FMS effectively, one must understand what each test assesses and how it is scored.

The scoring system is standardized to ensure consistency across different clinicians. Every test is graded on a straightforward four-point scale from 0 to 3.

- Score 3: The movement is performed as intended, with no compensations.

- Score 2: The movement is completed, but with poor mechanics or compensation.

- Score 1: The individual is unable to complete the movement pattern as required.

- Score 0: Any pain reported during the movement automatically results in a zero. This score is a red flag indicating that a deeper clinical assessment is necessary.

This simple hierarchy allows for the establishment of a clear, repeatable baseline and provides a common language to discuss movement quality.

This shared vocabulary makes the FMS a powerful tool in a team setting. Now, let’s examine the specifics of the seven tests.

A Quick Reference Guide to the 7 FMS Tests

This table provides a summary of each FMS test, breaking down what each movement primarily assesses and the basic criteria for scoring.

| FMS Test | Primary Focus Area | Score 3 (Perfect) | Score 2 (Pass with Compensation) | Score 1 (Unable to Complete) | Score 0 (Pain) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Squat | Symmetrical mobility and stability of the hips, knees, and ankles. | Dowel stays overhead, torso parallel to shins, heels on the floor. | Limited movement, upper torso leans forward excessively. | Cannot maintain balance or complete the squat depth. | Pain reported. |

| Hurdle Step | Single-leg stability, coordination, and hip/knee/ankle mobility. | Hips, knees, and ankles aligned; minimal spine movement. | Movement in the lumbar spine, loss of balance, foot hits the hurdle. | Cannot clear the hurdle or maintain stance leg stability. | Pain reported. |

| In-line Lunge | Hip and ankle stability, thoracic spine mobility. | Minimal torso movement, stable stance, feet remain in line. | Significant torso movement, loss of balance, feet move off the line. | Cannot complete the lunge or maintain the starting position. | Pain reported. |

| Shoulder Mobility | Multi-planar shoulder range of motion, scapular stability. | Fists are within one hand length of each other. | Fists are within one-and-a-half hand lengths. | Fists are greater than one-and-a-half hand lengths apart. | Pain reported. |

| ASLR | Active hamstring/calf flexibility and core stability. | Ankle is between mid-thigh and ASIS. | Ankle is between the knee and mid-thigh. | Ankle is below the joint line of the non-moving knee. | Pain reported. |

| Trunk Stability Push-up | Core stability in the sagittal plane during a push movement. | Body lifts as a unit with no lag in the spine (Men: thumbs at forehead; Women: thumbs at chin). | Body lifts as a unit (Men: thumbs at chin; Women: thumbs at clavicle). | Unable to perform a push-up while maintaining a rigid torso. | Pain reported. |

| Rotary Stability | Multi-planar core stability during asymmetrical movement. | Performs a correct unilateral repetition. | Performs a correct diagonal repetition. | Unable to perform a correct diagonal repetition. | Pain reported. |

These tests should be viewed not as a final diagnosis, but as a series of questions posed to the body, with the answers guiding subsequent steps.

A Deeper Dive into the Seven Movements

Each of the seven movements provides a unique window into how the body functions as an integrated system. Some are designed to test symmetrical patterns, while others are effective at exposing asymmetries between the left and right sides.

1. Deep Squat: This is a key test for evaluating full-body, symmetrical movement. It requires functional mobility and stability from the hips, knees, and ankles, while the thoracic spine and shoulders work together to maintain alignment.

2. Hurdle Step: This movement assesses the coordination and stability needed to step over an obstacle. It challenges the mobility of one leg while requiring the other to provide stability through the pelvis and core.

3. In-line Lunge: By narrowing the stance, this movement places the stability of the foot, ankle, knee, and hip under scrutiny. It also provides insight into thoracic spine mobility and hip flexor flexibility.

The goal is not merely to achieve a high score, but to understand why a score is low. A low score on the Hurdle Step, for instance, suggests a need to investigate hip mobility or single-leg pelvic control more deeply.

4. Shoulder Mobility: This test examines the complex, multi-planar range of motion in the shoulder, combining internal rotation and adduction with external rotation and abduction. It also requires good scapular mobility and thoracic extension. For those interested in precisely measuring joint angles, our guide on conducting a range of motion test is a valuable resource.

5. Active Straight Leg Raise (ASLR): The ASLR is excellent for assessing active hamstring and calf flexibility while maintaining a stable pelvis. It focuses on how well an individual can actively control limb movement separate from their trunk.

6. Trunk Stability Push-up: This is not a test of strength. It is about the core's ability to stabilize the spine while the upper body performs a pushing motion. Any sagging in the hips or low back indicates a lack of core control.

7. Rotary Stability: This test challenges multi-planar core stability during a combined arm and leg movement. It highlights the body's ability to resist rotation and maintain alignment during asymmetrical tasks, which is crucial for almost every sport.

By systematically working through these seven patterns, a practitioner can quickly build a comprehensive picture of an individual's movement competency, flagging asymmetries and dysfunctions that warrant a closer look.

How to Interpret FMS Scores With Scientific Evidence

Once the Functional Movement Screen is completed and the scores are recorded, the interpretive work begins. A key question is what these numbers mean in a real-world context. While it may be tempting to view the total score as a predictor of future injuries, scientific evidence suggests a more nuanced and useful interpretation.

The debate over the FMS's ability to predict injuries has been ongoing. Early interpretations often cited a composite score of 14 or below as a significant risk indicator. However, a systematic review and meta-analysis of the available literature concluded that the FMS should not be used to predict injury (1).

This does not diminish the value of the FMS. Instead, it reframes its application. Rather than asking, "Will this person get injured?" a more appropriate question is, "What does this screen reveal about how this person currently moves?"

Movement Competency Over Injury Prediction

The FMS excels at providing a quick, qualitative snapshot of an individual's movement patterns. It is effective for identifying "weak links" such as asymmetries, mobility restrictions, or stability issues that lead to inefficient compensations.

For example, a low score on the deep squat does not automatically mean a knee injury is imminent. It does, however, indicate that the individual may lack essential components like ankle dorsiflexion, hip mobility, or thoracic extension to perform this fundamental movement correctly. This is valuable clinical information.

The FMS can be understood as a tool for identifying risk factors. It alerts you to the presence of poor movement quality, asymmetry, and pain, allowing for intervention, rather than predicting exactly when or where an injury will occur.

When the focus shifts from injury prediction to improving movement competency, the FMS becomes a roadmap for building more resilient individuals. Correcting a significant right-to-left asymmetry or a notable mobility deficit is a tangible improvement that benefits an athlete or patient's overall function. To understand how scores compare across populations, it is helpful to grasp the concept of normative data in clinical assessments.

Using Evidence to Prioritize Interventions

While the FMS may not be a perfect predictive tool for all individuals, research indicates it can be valuable for identifying at-risk subgroups and guiding the allocation of resources. One study in the journal Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise found the FMS identified a subgroup of young, healthy military officer candidates as having a high injury risk, allowing medical staff to target prevention efforts more effectively (2).

This same research highlights the screen's ability to detect existing pain. In a large cohort of officer candidates, the FMS flagged movement-related pain, which is a known inhibitor of proper motor control and a clear sign that further evaluation is needed (2).

Ultimately, interpreting FMS scores based on scientific evidence means leveraging its strengths. Use it to establish a baseline for movement quality, identify asymmetries, uncover pain, and develop a more informed corrective exercise plan. From this perspective, the Functional Movement Screen remains an important tool for professionals dedicated to improving human movement.

References

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, Validity, and Injury Predictive Value of the Functional Movement Screen: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

- O'Connor FG, Deuster PA, Davis J, Pappas CG, Knapik JJ. Functional movement screening: predicting injuries in officer candidates. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(12):2224-2230.

Designing Corrective Strategies From FMS Results

An FMS score sheet is more than a set of numbers; it's a blueprint for action. The results can be translated into a targeted, effective corrective exercise program by following a systematic approach that addresses the most critical issues first.

This process is not about "training the test" to improve a score. It is about addressing the root cause of the dysfunction that the screen identified. A well-designed strategy corrects the underlying limitations, leading to authentic and lasting improvements in movement quality.

The FMS Corrective Hierarchy

The FMS corrective philosophy follows a clear and logical progression. It prioritizes issues to ensure that stability is not built on a painful or immobile foundation.

The hierarchy is structured as follows:

- Address Pain (Score 0): Any movement that scores a '0' due to pain is the top priority. Pain can inhibit proper motor control and is a clear signal that a thorough clinical evaluation by a qualified professional is required.

- Improve Mobility (Score 1): Next are movements that scored a '1'. These scores often point to significant mobility restrictions in the joints or surrounding tissues. A stable pattern cannot be trained if the body physically lacks the required range of motion.

- Enhance Motor Control (Asymmetrical Score 2): Finally, asymmetries where one side scores a '2' and the other a '3' are addressed. A score of '2' indicates the person can perform the movement but with compensation. This imbalance suggests a motor control or stability deficit that needs correction.

This systematic approach helps avoid the common mistake of applying advanced stability exercises to a fundamental mobility problem. Mastering the basics is a prerequisite for more complex training.

From Score to Specific Action

A score indicates where to look, while the observed compensations during the screen suggest what to fix.

For example, an individual scores a '1' on the Active Straight Leg Raise (ASLR). This points to a limitation in active hamstring and calf flexibility while maintaining core and pelvic stability. Observations such as the opposite leg lifting off the floor or the pelvis tilting provide additional clues.

A corrective strategy in this case should be comprehensive.

Example Corrective Plan for a Score of '1' on ASLR:

- Soft Tissue Work: Begin with foam rolling the hamstrings and calves to address potential tissue restrictions.

- Targeted Mobility Drills: Implement active drills like leg swings or supine active leg lowers to improve dynamic flexibility.

- Core Engagement: Incorporate exercises like dead bugs or bird-dogs to teach the client how to stabilize their pelvis and core during limb movement.

Addressing Asymmetry and Stability

Consider another scenario where someone scores differently on the Rotary Stability test, with a '2' on the right and a '3' on the left. This asymmetry highlights a deficit in core stability on one side, specifically in resisting rotation. The goal is not about building brute strength, but about fine-tuning the neuromuscular control needed for stability during movement.

A targeted plan might include:

- Breathing and Bracing: Return to basic drills like 90/90 hip lift breathing to teach proper core engagement.

- Anti-Rotation Exercises: Progress to exercises like Pallof presses or challenging bird-dog variations that require the core to resist rotational forces.

- Motor Patterning: Use movements like quadruped rocking or crawling variations to re-educate the coordination between the hips, core, and shoulders.

By adhering to this hierarchy, clinicians and coaches can design intelligent programs that address the root cause of dysfunction, leading to more resilient athletes and healthier clients.

Enhancing The FMS With Objective Measurement

The Functional Movement Screen provides an excellent qualitative assessment of movement. However, its reliance on visual observation and a 0-3 scale introduces a degree of subjectivity. To elevate assessments and create highly precise corrective programs, it is beneficial to pair the FMS with objective measurement tools. This approach transforms observation into quantifiable data.

This method does not replace the FMS; it enhances it. The screen acts as an initial sweep to identify areas requiring closer examination. Once a potential issue is flagged, technology provides the means to analyze the problem in greater detail. This moves the assessment from subjective impressions to concrete metrics, which is fundamental for tracking progress and making informed clinical decisions.

From Observation to Quantification

The power of this integrated approach lies in quantifying the why behind a low FMS score. When a compensation is observed, a digital tool can immediately measure the underlying physical capacity, creating a richer and more actionable data set.

For example, a score of '1' on the Shoulder Mobility test indicates a significant limitation. The next question is, "Why?" Is it due to a lack of thoracic extension, or a specific limitation in shoulder internal or external rotation? A digital goniometer can provide a precise range of motion measurement in degrees, eliminating guesswork.

This logic applies to all tests. A poor score on the Trunk Stability Push-up might suggest "core weakness." Instead of a simple notation, a digital dynamometer can be used for an isometric push-up hold test, measuring the exact force output and endurance. This provides a clear, objective baseline for intervention.

The Power of Precision Tools

Integrating modern measurement tools directly addresses the inherent limitations of a purely observational screen. While research indicates the FMS has strong reliability among trained practitioners, scores can vary between raters with different experience levels (1). Objective tools provide unambiguous data.

Here’s how key technologies can transform the screening process:

- Digital Goniometers: These tools offer high accuracy for measuring joint range of motion. When the Active Straight Leg Raise is limited, a goniometer can quantify active hip flexion and help determine if it is a true hamstring issue, leading to a more targeted intervention.

- Digital Dynamometers: For tests challenging stability, a dynamometer is ideal for measuring isometric strength. It can quantify core strength during a plank, grip strength, or isolate glute medius force production if the Hurdle Step reveals pelvic instability.

- Force Plates: For a deeper analysis, advanced tools like force plates measure ground reaction forces and balance. If an In-line Lunge reveals poor stability, a single-leg balance test on a force plate can objectively measure postural sway, offering a sensitive metric for tracking motor control improvements.

By adding objective numbers to FMS findings, you create a powerful feedback loop. You can show an athlete or patient exactly how much their ankle dorsiflexion has improved or how their core strength has increased. This makes progress tangible and motivating.

Creating a Data-Driven Rehabilitation Journey

This blend of qualitative screening and quantitative measurement builds a robust framework for rehabilitation and performance training. The FMS identifies the faulty pattern, and objective tools measure the parts contributing to that pattern. This detailed understanding allows for highly specific corrective exercises and a reliable way to monitor their effectiveness.

As a clinician, you can document progress at every visit, providing clear evidence of improvement that supports clinical reasoning. This approach moves beyond simply chasing a better FMS score and focuses on improving the measurable physical capacities that create healthy, efficient movement. Understanding the central role of data is key to modern practice, and you can explore the objective of measurement in clinical settings to build on this knowledge.

Ultimately, combining the FMS with objective measurement offers a holistic view of movement patterns backed by precise, repeatable data.

References

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, Validity, and Injury Predictive Value of the Functional Movement Screen A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

Using FMS Data To Guide Return-To-Sport Decisions

A comprehensive rehabilitation plan does not conclude when pain subsides. It ends when an athlete is prepared to handle the specific demands of their sport. Tracking an athlete with the Functional Movement Screen and objective data is critical for making informed return-to-sport (RTS) decisions. This process builds an evidence-based case that an athlete is not only pain-free but also moving competently and symmetrically.

Pairing periodic FMS re-screens with consistent, quantitative measurements creates a powerful system for monitoring progress. This documented journey provides clear, tangible proof of improvement, which is essential for clinical decision-making and for keeping an athlete motivated throughout their recovery.

Beyond Subjective Assessment

Historically, many RTS decisions were based heavily on timelines and subjective reports from the athlete. While these factors are important, relying solely on them can overlook underlying movement issues that may predispose an athlete to re-injury. The FMS, when combined with objective data, provides a more rigorous and safer standard for clearing an athlete for participation.

This modern approach moves beyond simple "pass/fail" thinking and instead builds a complete profile of the athlete's movement health.

Establishing Clear RTS Criteria

A data-driven RTS protocol establishes a clear set of benchmarks that must be met before an athlete is cleared. This removes ambiguity and facilitates communication among the athlete, clinician, and coach. A strong, evidence-based protocol should include several key components.

Key Return-to-Sport Benchmarks:

- A Pain-Free Screen: This is a non-negotiable first requirement. A completely pain-free FMS is essential. Any score of '0' indicates that the underlying issue has not been fully resolved.

- Symmetrical Movement: The athlete must demonstrate symmetry on all relevant FMS tests, with no significant differences between their left and right sides. An asymmetrical score, such as a '2' on one side and a '3' on the other for the Hurdle Step, suggests a motor control deficit that requires further work.

- Meeting Objective Benchmarks: This is where quantitative data is crucial. The athlete’s objective data—strength, range of motion, balance metrics—should meet or exceed their pre-injury baseline or established sport-specific norms. A 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis highlighted that while the FMS has good reliability, it is best used alongside other objective measures to create a complete risk profile (1).

An athlete who achieves a symmetrical, pain-free score of 16 on the FMS and has dynamometry readings showing their quadriceps strength is within 5% of their uninjured leg presents a much stronger case for a safe return than an athlete who simply reports feeling "good to go."

This layered approach ensures that decisions are based on evidence, not conjecture. Documenting this journey builds confidence for the entire support team and provides the athlete with the assurance that they have earned their return to sport. When an athlete sees data proving their progress, their mindset can shift from hoping they are ready to knowing they are ready.

References

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Dhawan A. Reliability, Validity, and Injury Predictive Value of the Functional Movement Screen A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45(3):725-732.

Common Questions About Functional Movement Screening

As Functional Movement Screening becomes more common in clinics and training facilities, several questions often arise. Addressing these points can help ensure the screen is used responsibly and effectively.

Can The FMS Predict Exactly Who Will Get Injured?

No, the FMS was not designed to predict specific injuries with certainty. A systematic review and meta-analysis of scientific literature has shown that while low scores may be associated with an increased statistical risk in some populations, the FMS's ability to predict a specific injury for a particular individual is limited (1).

The primary value of the FMS lies in identifying current, observable issues: significant movement dysfunctions, asymmetries, and underlying pain. These are recognized risk factors. The screen functions as an alert system for potential danger, allowing for intervention, rather than a tool for forecasting a specific event.

How Often Should Someone Be Screened?

The frequency of screening depends on the context. For athletes, a pre-season screen is valuable for establishing a baseline. A mid-season re-screen can provide insight into how competition, fatigue, or minor injuries have affected their movement patterns.

In a clinical rehabilitation setting, the FMS is useful for the initial evaluation. After a block of corrective exercise—typically around 4-6 weeks—a re-screen can offer objective evidence of progress and inform the next phase of the program.

The FMS is most valuable when used to establish a baseline and assess meaningful change over time, rather than as a daily or weekly assessment.

Is The FMS Still Useful With Other Assessments?

Yes, the FMS is highly effective when used as part of a comprehensive assessment battery. It provides a broad overview of fundamental movement patterns but is not intended to be a deep diagnostic tool.

Its function is to identify areas that require further investigation. For instance, if the screen reveals a poor squat pattern, this is a cue to use more precise tools. A digital goniometer could be used to measure exact joint angles, or a dynamometer to test specific muscle strength. The FMS helps identify the problem area, allowing the clinician to focus on it with more specific instruments.

At Meloq, we build the objective tools that deliver the hard data needed to complement your functional screening. Our digital goniometers and dynamometers replace subjective guesswork with precise, repeatable measurements. This empowers you to quantify progress and make clinical decisions with unshakable confidence. Discover how to elevate your assessments at meloqdevices.com.