A Clinician's Guide to Functional Movement Screen Tests

Team Meloq

Author

The Functional Movement Screen (FMS) is a system designed to observe and rate fundamental movement patterns. It is a series of standardized tests that help clinicians and coaches identify significant limitations and asymmetries. The FMS can be viewed as a method for identifying potential "weak links" in an individual's kinetic chain before they may contribute to a larger issue.

It is important to understand that the FMS is a screening tool, not a diagnostic one. It does not aim to pinpoint a specific injury. Instead, it observes and ranks the quality of movement to establish a clear baseline of an individual's movement competency.

Decoding The Functional Movement Screen

The FMS acts as a quality check on the body's fundamental movement capabilities. Just as letters must be formed correctly to write a clear sentence, basic movements must be performed proficiently to execute complex, athletic actions safely and efficiently. The screen helps bridge the gap between a standard pre-participation physical and more performance-specific testing.

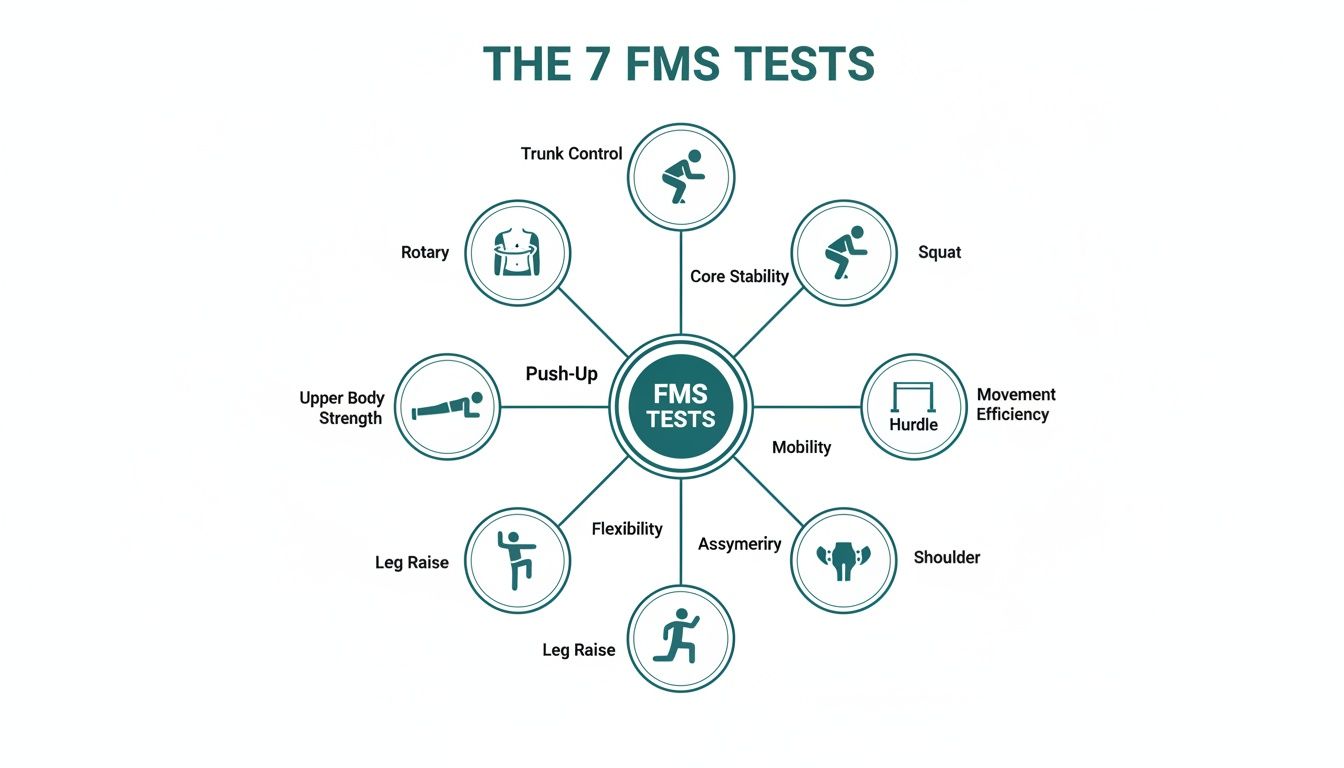

The FMS is built around seven fundamental movement tests, each scored on a simple 0-3 scale. This provides clinicians and coaches with a repeatable, objective method to observe, rate, and document an individual's movement capabilities.

The Purpose Behind The Screen

The primary goal of the FMS is not to diagnose an injury. It is to identify major limitations or imbalances that might be associated with an increased risk of non-contact injury (1). The strength of the FMS lies in its systematic and consistent approach.

The key objectives are:

- Establish a Movement Baseline: The screen provides a snapshot of a person's current movement capacity, which is essential for tracking progress over time.

- Identify Major Limitations: It is effective at flagging poor mobility in key areas such as the hips, shoulders, and ankles.

- Detect Asymmetries: It can quickly uncover significant differences in movement quality between the left and right sides of the body, which may lead to compensatory patterns.

A critical component of the scoring system is the '0' score. If an individual reports pain during any of the seven movements, they receive a score of zero. This score is an immediate red flag, signaling that a full clinical evaluation by a physiotherapist or another qualified medical professional is required before training proceeds.

This pain-clearing mechanism ensures that safety remains the top priority.

Beyond Injury Prediction

While early research suggested a link between low FMS scores (typically a composite score of 14 or less out of 21) and a higher risk of injury, scientific understanding has evolved. A more modern perspective is to use the FMS less as a tool for predicting injury and more as a guide for developing corrective exercise strategies (2).

When a "weak link" is identified—for example, poor ankle mobility that compromises a deep squat—it provides a clear starting point for intervention. A clinician can then design a targeted program to address that specific deficit. By improving the fundamental pattern, the individual can build strength and skill on a more stable and efficient foundation. This makes the FMS a valuable component of a comprehensive musculoskeletal assessment.

References

- Kiesel K, Plisky PJ, Voight ML. Can Serious Injury in Professional Football be Predicted by a Preseason Functional Movement Screen? North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2007;2(3):147-158.

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Miller TL. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(3):725-732.

A Detailed Breakdown Of The Seven FMS Tests

The Functional Movement Screen is composed of seven fundamental movement patterns, each designed to challenge the body in a specific way. These tests can be thought of not as isolated exercises, but as inquiries into an individual's mobility, stability, and motor control.

Before proceeding to the seven core tests, it is essential to discuss the clearing tests. These are non-negotiable safety checks performed alongside the shoulder mobility, trunk stability push-up, and rotary stability tests. If an individual reports any pain during a clearing test, they are assigned a score of zero for the associated movement, which is an immediate signal that a full clinical assessment is necessary.

With this crucial safety protocol in place, we can examine each of the seven tests to understand what information they provide.

The 7 Core Functional Movement Screen Tests at a Glance

This table summarizes the seven FMS tests, providing a quick reference for the primary goal of each movement and the key areas being assessed.

| FMS Test | Primary Movement Pattern Assessed | Key Areas of Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Squat | Full-body mechanics, flexion, and alignment | Hips, knees, ankles, shoulders, thoracic spine |

| Hurdle Step | Single-leg mobility and stability | Hip mobility, pelvic and core stability |

| In-Line Lunge | Split-stance stability and mobility | Hips, ankles, core, knee stability |

| Shoulder Mobility | Reciprocal upper-body range of motion | Glenohumeral joint, scapula, thoracic spine |

| Active Straight-Leg Raise | Dissociation of limbs and core stability | Hamstring and calf flexibility, hip mobility, core control |

| Trunk Stability Push-Up | Sagittal plane core stabilization | Core and spinal stability during upper-body movement |

| Rotary Stability | Multi-planar core and limb control | Reflexive core stabilization, resisting rotation |

Each test reveals a different piece of the movement puzzle. Let’s now look at how they accomplish this.

1. Deep Squat

The Deep Squat is the first test, providing a comprehensive view of total body mechanics. It assesses symmetrical, functional mobility in the hips, knees, and ankles simultaneously. It also challenges the stability of the shoulders and the motor control required to maintain thoracic spine extension.

The individual stands with feet shoulder-width apart, holding a dowel overhead. They then squat as deeply as possible while keeping their heels flat, chest up, and the dowel directly overhead. This pattern is fundamental to many daily and athletic activities.

2. Hurdle Step

The Hurdle Step assesses movement on a single leg, which is an effective way to expose asymmetries between the left and right sides. It demands coordinated mobility in one hip while the core, pelvis, and stance leg must work to maintain stability.

A string is set at the height of the individual's tibial tuberosity. They are required to step cleanly over it without touching the string, all while staying upright with minimal sway. This mimics the mechanics of acceleration and sprinting, where single-leg stability is critical.

3. In-Line Lunge

The In-Line Lunge places the body into a narrow, split-stance position, immediately increasing the demand on balance and stability. This test is excellent for observing hip and ankle mobility, quadriceps flexibility, and knee and core stability under a challenging stance.

The individual lines one foot directly in front of the other while holding a dowel behind their back, maintaining contact with their head, upper back, and sacrum. From there, they lunge straight down. This is highly relevant for sports involving frequent deceleration and changes of direction from a split-stance position.

4. Shoulder Mobility

This test examines the reciprocal movement pattern of the shoulders. It assesses the combined range of motion of the glenohumeral joint, the scapulothoracic joint, and the thoracic spine.

To perform the test, the individual makes a fist and attempts to bring their hands as close together as possible behind their back—one reaching over the top, the other from underneath. The distance between the fists is measured. This pattern is fundamental for throwing, swimming, and many overhead athletic activities. For a deeper understanding of how these joints are assessed, you can learn more about a complete range of motion test.

5. Active Straight-Leg Raise

The Active Straight-Leg Raise assesses the ability to actively utilize hamstring and calf flexibility while maintaining a stable pelvis and core. It is more than a simple flexibility test; it evaluates the ability to move the lower limbs independently from a stable trunk.

Lying supine, the individual raises one leg as high as possible without bending the knee or allowing the opposite leg to lift from the floor. This provides a clear view of functional hip mobility and posterior chain flexibility, a significant factor in proper running mechanics.

6. Trunk Stability Push-Up

This test assesses the ability to stabilize the spine while performing an upper-body pushing movement. It is a measure of core stability in the sagittal plane, checking for any "sag" in the hips or "lag" in the spine.

From a standard push-up position, the individual lowers their body as a single unit and pushes back up. Hand placement is adjusted for males and females to account for general differences in upper-body strength. A stable trunk is the foundation for transferring force from the ground up, which is essential for powerful athletic movements.

7. Rotary Stability

The Rotary Stability test examines multi-planar core stability during a combined upper and lower body movement. It challenges the body's ability to resist rotation and maintain balance from a quadruped position.

From a hands-and-knees position, the person extends the arm and leg on the same side, then brings the elbow and knee together to touch. This screen provides a snapshot of the reflexive core control needed for the diagonal movements that are a cornerstone of many sports.

Interpreting FMS Scores and Understanding The Evidence

After administering the seven functional movement screen tests, the result is a set of scores. The clinical skill lies in interpreting these numbers to form a clear, actionable understanding of an individual's movement patterns.

The FMS yields a composite score out of 21, offering a quick overview of overall movement quality. For many years, a score of 14 or below was widely considered a threshold that suggested a higher risk of injury, a benchmark that became prevalent in physiotherapy and strength and conditioning.

The Science Behind The Score

This threshold was not arbitrary. An influential 2007 study was among the first to report that athletes scoring 14 or less had a significantly higher incidence of serious injury (1). This publication helped establish a standard that has guided clinical protocols.

Subsequent research has examined this finding across various populations. One systematic review supported the observation of higher injury rates for those scoring ≤14 (3), and another study on female collegiate athletes reported a nearly four-fold increased risk of a lower-extremity injury if their score was below this mark (4). You can explore the findings on injury risk and FMS scores in more detail.

However, it is important to interpret this score with caution. The FMS is not a diagnostic tool and its predictive power can vary depending on the sport, age, and level of competition. A low score should be seen as an indicator to investigate further, not as a definitive prediction of future injury.

Moving Beyond a Single Number

Relying solely on the total score out of 21 can mean overlooking the most valuable information the FMS provides. The real insights are often found in the individual test scores, especially when asymmetries or major limitations are identified.

An asymmetry is a score difference between the left and right sides on tests such as the Hurdle Step, Shoulder Mobility, or In-Line Lunge. These imbalances can be more telling than a low overall score, as they may indicate compensatory movement patterns that could lead to overuse and strain.

The goal is not necessarily to achieve a perfect score of 21. A higher priority should be to identify the most significant movement problem—what the FMS system terms the "weakest link"—and address that first. A symmetrical score of all 2s may be preferable to a higher total score that masks a significant asymmetry.

This diagram illustrates the seven tests, each challenging the body's movement system in a unique way.

From the full-body coordination of a deep squat to the specific flexibility required for a leg raise, each test contributes a piece to the overall movement puzzle.

What Individual Low Scores Reveal

A score of '1' on any test points directly to a fundamental problem with either mobility or stability, providing a clear starting point for intervention.

Here is a general interpretation of these signs:

- Active Straight-Leg Raise (Score of 1): This often indicates limited hamstring and calf flexibility, but it can also relate to a lack of core and pelvic stability during leg movement.

- Hurdle Step (Asymmetry): A difference in score between sides can suggest hip mobility discrepancies or poor single-leg stability.

- Shoulder Mobility (Score of 1): This is frequently associated with a thoracic spine mobility issue rather than a primary shoulder joint problem.

By analyzing the scores in this manner, clinicians can develop a highly targeted corrective plan. For additional context, understanding the definition of normative data can help in comparing a client's score to a wider population.

References

- Kiesel K, Plisky PJ, Voight ML. Can Serious Injury in Professional Football be Predicted by a Preseason Functional Movement Screen? North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2007;2(3):147-158.

- Teyhen DS, Shaffer SW, Lorenson CL, et al. The Functional Movement Screen: a reliability study. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2009;39(8):578-586.

- Chorba RS, Chorba DJ, Bouillon LE, et al. Use of a functional movement screening tool to determine injury risk in female collegiate athletes. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2010;5(2):47-54.

Augmenting The FMS With Objective Measurement Tools

The Functional Movement Screen provides an excellent qualitative snapshot of an individual's movement. Its 3-2-1 scoring system creates a common language for discussing movement quality. However, as a visual assessment, it has inherent limitations.

A primary consideration is inter-rater reliability. One clinician's score of "2" might be another's "1," which can lead to inconsistencies. This is not a critique of the FMS itself, but a reality of human observation. The naked eye may miss subtle compensations, and tracking small, incremental improvements over time can be difficult. How do we determine the reason behind a poor score?

This is where objective digital measurement tools become valuable. They can elevate the FMS from a simple screen to a data-rich assessment.

Moving From Observation To Quantification

Consider a client who scores a '1' on the Deep Squat. Clinical experience might suggest restricted ankle dorsiflexion. But how restricted is it? Is the left ankle more limited than the right? And how can one demonstrate that corrective exercises are effective?

Objective tools are designed to answer these questions. They replace estimations with precise, repeatable data, providing quantitative evidence to support clinical observations.

By adding a layer of objective data, a subjective observation is transformed into a measurable fact. This shift is crucial for validating corrective strategies, enhancing clinical decision-making, and providing clear, motivating feedback to patients and athletes.

The FMS identifies the area of dysfunction, and objective tools provide the detailed evidence needed to understand and address it.

Key Tools For A Data-Driven FMS

Incorporating objective measures does not mean abandoning the FMS. These tools are used to investigate the specific limitations that the screen identifies. Here is how this synergy works in practice:

-

Digital Goniometers: These devices measure joint angles with high accuracy. If a client performs poorly on the Active Straight-Leg Raise, a digital goniometer can quantify the exact degrees of hip flexion or pinpoint a hamstring deficit. This establishes a solid baseline and offers an undeniable method for demonstrating progress.

-

Digital Dynamometers: When the Trunk Stability Push-Up or Rotary Stability test reveals weakness, a dynamometer can quantify it. Instead of merely noting an imbalance, one can measure the precise force output of the left side versus the right, providing a clear target for a strength program.

These instruments offer the granular detail required to build truly personalized programs. For those interested in the principles of force testing, our guide on what is force measurement is a great starting point.

The Clinical Advantages Of An Integrated Approach

Pairing the qualitative insights of the FMS with quantitative data creates a powerful assessment framework. The benefits extend beyond simply collecting more numbers.

1. Enhanced Reliability and Repeatability

Objective tools significantly improve both inter-rater (between different testers) and intra-rater (the same tester over time) reliability. A measurement of 15 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion is consistent, regardless of who performs the measurement or when it is taken. This consistency is a cornerstone of evidence-based practice.

2. Validated Corrective Strategies

With objective data, it is possible to prove that interventions are working. If a program is designed to improve thoracic spine rotation to address a '1' on the Shoulder Mobility screen, a measurable increase in range of motion can be demonstrated. It is no longer an estimation; it is a documented fact.

3. Improved Patient and Athlete Engagement

Seeing objective progress can be highly motivating. When clients see their hip flexion measurement improve by 10 degrees or their core strength numbers increase, it reinforces their efforts and builds trust in the practitioner's expertise.

By augmenting the functional movement screen tests with these tools, clinicians can paint a more complete and compelling picture of human movement. This integrated approach leads to more precise interventions, clearer progress tracking, and ultimately, better outcomes.

Common Pitfalls in FMS Administration and How to Nail It Every Time

The value of the Functional Movement Screen is directly related to the precision with which it is administered. Like any standardized test, accuracy is paramount. Even small deviations from the protocol can compromise the results, turning a clear snapshot of movement into an unreliable assessment.

One of the most common errors is providing inconsistent or excessive verbal cueing. The goal is to observe how an individual naturally moves, not to coach them into a perfect score. Cues like "Push your knees out" or "Keep your chest up" during the Deep Squat fundamentally alter the test. It ceases to be a screen and becomes a training session, invalidating the results.

The Devil's in the Details

Beyond improper cueing, several other common mistakes can undermine the integrity of functional movement screen tests. These often occur when the process is rushed or the strict scoring criteria are not fully adhered to.

-

Sloppy Equipment Setup: Using a dowel of the wrong length, setting the hurdle string at an incorrect height, or failing to use the board for the In-Line Lunge may seem like minor issues, but they significantly alter the movement's difficulty and mechanics. Precision is non-negotiable for ensuring results are comparable over time.

-

"Generous" Scoring: The distinction between a '2' (performed with compensation) and a '1' (unable to complete the pattern cleanly) can seem subjective. However, giving the benefit of the doubt is a significant error, as it often masks the very movement dysfunction the screen is designed to identify.

-

Skipping or Rushing Clearing Tests: The three clearing tests are mandatory safety checks, not optional extras. If a client reports pain, the score is a '0', and that portion of the screen concludes. Ignoring this step not only misses a critical red flag but also violates a core principle of the system.

Creating a Bulletproof Protocol

Avoiding these pitfalls requires standardizing the process and creating a repeatable testing environment. Treating every FMS administration as a scientific protocol is key. Using a checklist can ensure that every step is followed consistently.

The purpose of the FMS is to find the 'weakest link' in the kinetic chain. When administration is inconsistent, the weakest link is not the client—it is the screening process itself.

A disciplined approach greatly improves intra-rater reliability, meaning your own consistency over time. When your process is identical every time, you can be confident that a change in score reflects a genuine change in the client's movement, not a variation in your testing procedure.

The scientific conversation around FMS scoring and injury risk is continually evolving. For example, a 2023 study of 809 athletes reported an average FMS score of 13.8 ± 2.5, with only about 25% falling below revised risk thresholds, suggesting that the screen's predictive utility can vary significantly by sport (1).

This underscores why precise, unbiased administration is so crucial. By mastering the details, you ensure the data you collect is a true reflection of your client's capacity, allowing for the development of effective, targeted programs. You can find more insights on FMS scores and injury risk across different sports in the full study.

References

- Lovalekar M, Wirt MD, Gunn S, et al. Functional movement screen scores and injury risk in sport: a systematic review with meta-analysis. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2023;18(3):547-569.

Turning FMS Results Into Actionable Corrective Strategies

Administering the functional movement screen tests is the first step; the true clinical value lies in translating that data into a smart, targeted plan. The screen identifies what the issue is; the corrective strategy addresses how to fix it. The FMS is the map, not the destination.

A logical, hierarchical approach to rebuilding movement can be highly effective. This framework ensures that interventions address the root cause of the dysfunction rather than just the symptoms, and avoids building strength on top of a faulty foundation.

A Three-Tiered Corrective Framework

This process can be compared to building a house: a solid foundation must be laid before the walls are erected. The same principle applies to the human body, where the most fundamental issues must be addressed first.

-

Address Mobility Limitations: If a joint lacks the necessary range of motion to achieve a position, the body will inevitably compensate. A score of '1' on the Shoulder Mobility test, for example, often points to poor thoracic spine extension. The first priority is to improve mobility in that area before attempting overhead strengthening exercises.

-

Build Motor Control and Stability: Once adequate range of motion is available, the body must learn to control it. This involves improving stability around the joints and engaging the core. It is the distinction between passively having a range of motion and actively controlling it.

-

Reinforce Functional Patterns: Only after establishing mobility and stability should the pattern be loaded. This phase involves grooving the complete movement and building strength on a solid base.

This tiered system creates a durable and efficient foundation, ensuring each correction builds upon the last.

From Scores to Specifics

So, how does this framework connect to FMS results? A low score on any test is a direct signal indicating where to focus corrective efforts.

A low FMS score is not a verdict; it is a starting point. It provides a roadmap that guides you directly to the most significant movement restriction, allowing for a highly efficient and targeted intervention strategy.

For example, a score of '1' or a significant asymmetry on the In-Line Lunge immediately flags poor stability in a split stance. This is the cue to program exercises that challenge the core, hips, and ankles in precisely that position.

Similarly, a low score on Rotary Stability indicates that the core is not reflexively engaging to resist rotation. When balance is a key issue, our guide to balancing exercises for athletes can provide effective intervention strategies.

By systematically addressing the weakest links revealed by the FMS, practitioners can move from guessing to creating truly individualized programs that improve movement quality and help mitigate injury risk.

Your Top FMS Questions, Answered

Let's address some of the most common questions clinicians and athletes have when they begin using the functional movement screen tests. These are concise, evidence-informed answers to help clarify the application of the FMS.

Who Is The FMS For?

The FMS was designed to assess fundamental movement in a broad range of individuals, not just elite athletes. It is applicable to anyone who requires durability for their occupation or lifestyle, including tactical professionals like firefighters, manual laborers, and recreational athletes (1).

Screening is generally recommended for individuals aged 14 and older, as younger children may find some of the technical aspects of the tests challenging. The FMS is also a valuable tool for older adults, providing a clear way to track age-related changes in mobility and design programs to maintain an active and independent lifestyle.

How Does The FMS Differ From An Orthopedic Exam?

This is a crucial distinction. An orthopedic exam is a diagnostic process conducted by a medical professional to identify a specific injury or pathology that is already causing pain or symptoms.

The FMS, by contrast, is a screening tool. Its primary purpose is to identify movement limitations and asymmetries in individuals who are asymptomatic. If pain is reported during any of the seven tests (resulting in a '0' score), the screen is stopped. This serves as a red flag indicating the need for a full clinical evaluation.

Does A Low Score Guarantee An Injury?

No, a low FMS score does not guarantee a future injury. It is a risk factor, not a predictive certainty. While early research linked scores of 14 or below to a higher likelihood of injury, the scientific conversation has since evolved (2).

Today, a low score is viewed as one valuable piece of a larger puzzle. It highlights potential "weak links" in the kinetic chain that could become problematic under physical stress. However, it must be considered in conjunction with other factors, such as training load, sport-specific demands, and personal injury history, to build a complete risk profile.

How Often Should I Re-Screen?

Movement quality is dynamic and can fluctuate with training, fatigue, and other life factors. Therefore, the FMS should not be a one-time assessment. It is a tool for tracking progress and identifying new issues before they become significant problems.

Key times for re-screening include:

- Pre-season: To establish a crucial baseline.

- Mid-season: Particularly if a decline in performance or minor nagging issues are observed.

- Post-injury: To ensure quality movement has been fully restored before a return to full activity.

References

- Cook G, Burton L, Hoogenboom B. Pre-participation screening: the use of fundamental movements as an assessment of function - part 1. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2006;1(2):62-72.

- Bonazza NA, Smuin D, Onks CA, Silvis ML, Miller TL. Reliability, validity, and injury predictive value of the functional movement screen: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2017;45(3):725-732.

At Meloq, we view the FMS as an essential starting point for understanding movement quality. To truly quantify what is happening, however, measurement is key. While the FMS identifies the "what," our digital goniometers and dynamometers provide the "how much." They deliver the hard numbers needed to measure deficits precisely and track progress with undeniable accuracy. See how to elevate your assessments by visiting https://www.meloqdevices.com.