Fitness testing for seniors is not about training for an athletic competition. It is a strategic approach to measure physical function, identify potential health risks like falls, and create a personalised plan for maintaining independence and vitality. The focus is on quality of life, using targeted assessments to gain a real-world picture of an individual's strength, balance, endurance, and flexibility.

Why Fitness Testing Is Crucial for Healthy Aging

As we age, our bodies undergo natural changes. Activities that were once effortless, such as rising from a chair or carrying groceries, can become more challenging. This gradual shift underscores the importance of fitness testing for older adults, as it provides a clear, objective snapshot of an individual's current physical status. These tests are best viewed not as an exam, but as a personal health roadmap. They help identify strengths and, more importantly, flag specific weaknesses before they evolve into more significant issues. With a solid baseline, individuals and healthcare professionals can develop a focused plan that addresses specific needs.

A Proactive Approach to Independence

The primary goal is to preserve functional independence—the ability to perform daily activities safely and without assistance. For example, a low score on a balance test is more than a number; it can be an early indicator of an increased risk of falling (1). This proactive perspective allows for targeted interventions. Instead of reacting to a fall or injury, one can begin specific exercises to build stability and confidence. This shifts the paradigm from reactive healthcare to active prevention.

"Fitness testing provides the 'what' and the 'why' for an exercise program. It transforms a generic workout into a personalized prescription for maintaining vitality and independence for years to come."

Tailoring Your Fitness Journey

Because individuals age differently, a standardised, one-size-fits-all exercise plan is rarely effective long-term. Fitness testing provides the objective data needed to customise a program that is both safe and effective. The results guide decisions on which areas to prioritise, such as:

- Building lower body strength to make climbing stairs or getting out of a car easier.

- Improving dynamic balance to walk across uneven ground with confidence.

- Increasing aerobic endurance for longer walks, gardening, or playing with grandchildren.

- Enhancing flexibility to help ease stiffness and improve overall mobility.

In addition to individual tests, a holistic approach often involves comprehensive health and wellness programs for seniors. This focus is growing globally; in a 2021 survey of fitness trends, exercise programs for older adults ranked highly, indicating a significant rise in its perceived importance (2). With physical inactivity being a major risk factor for chronic conditions, these evidence-based assessments are critical tools (3).

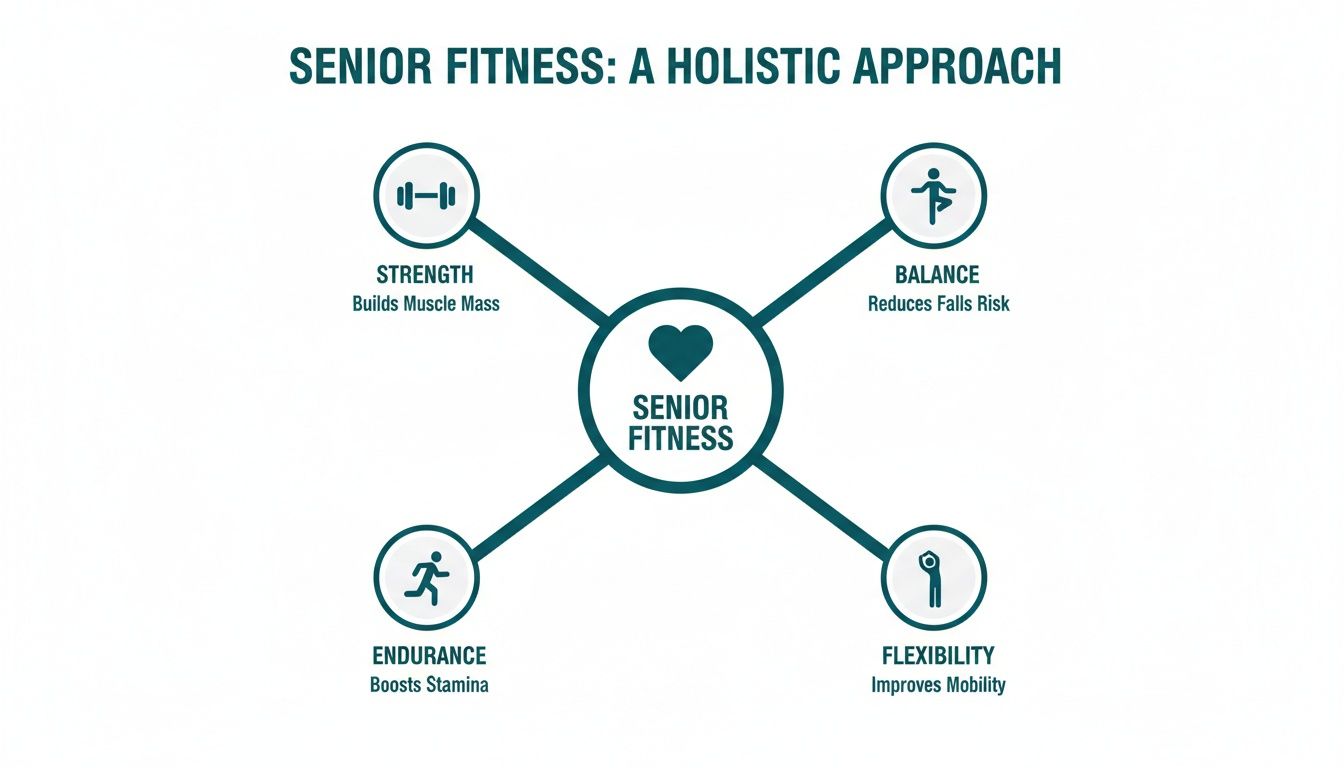

Understanding the Building Blocks of Senior Fitness

To create a meaningful fitness plan, one must first understand its core components. Senior fitness is built upon several interconnected elements: strength, balance, mobility, endurance, and flexibility. These concepts are not abstract; they are the foundations that empower individuals to live with confidence and ease.

The Power Reserve: Your Personal Strength

Strength can be considered a personal power reserve drawn upon for countless daily tasks. Lower body strength facilitates getting out of a chair, climbing stairs, or entering and exiting a vehicle. Upper body strength is required for lifting objects, carrying groceries, or holding a grandchild. When this reserve is depleted, these simple acts can become taxing or even hazardous.

The Twin Pillars: Balance and Mobility

Balance and mobility are the twin pillars of fall prevention and confident movement. Although closely related, they serve distinct functions.

- Balance is the ability to control the body's position, whether stationary or in motion. It maintains stability when reaching for an item on a high shelf.

- Mobility is the ability to move through an environment safely and efficiently, such as navigating a crowded room or walking on an uneven surface.

A decline in either of these areas can lead to hesitation, a fear of falling, and a reduction in activity levels (4). Rebuilding them is fundamental to staying active and safe.

The Engine: Aerobic Endurance

If strength is the power reserve, aerobic endurance is the engine. It determines how long one can sustain physical activity without becoming breathless or fatigued. Strong aerobic capacity is vital for activities like walking, gardening, or social outings. For seniors, understanding cardiovascular fitness is a cornerstone of healthy aging. Without adequate endurance, the range of possible activities may diminish.

"A well-rounded fitness assessment looks beyond just one number. It examines the interconnected system of strength, balance, endurance, and flexibility to create a complete picture of an individual's functional health."

The Key to Movement: Flexibility

Flexibility is the key to smooth, pain-free movement. It refers to the ability of joints to move through their full, intended range of motion. Good flexibility allows for bending to tie shoes, reaching to buckle a seatbelt, or turning one's head. When joints become stiff, movement is restricted, which can lead to compensatory patterns that cause strain or injury. For those interested, a deeper dive explains how to measure range of motion. By assessing each of these building blocks, it becomes possible to pinpoint specific areas for improvement and create a truly personalised action plan.

Essential Evidence-Based Fitness Tests You Should Know

Having covered the core fitness domains, we now turn to the practical, science-backed tools used to measure them. These are straightforward, functional assessments that provide clear, actionable insights. Each test offers a specific lens through which to view a particular aspect of fitness. The approach to senior fitness has evolved significantly from early batteries of tests. Modern assessments are critical for predicting functional decline and maintaining independence. For instance, research has established links between low performance on specific tests and an increased risk of falls (5).

Here is a look at some of the most respected and widely used fitness tests in physiotherapy and senior wellness programs.

This image highlights a key point: an effective fitness plan is not about isolating one area but about building a holistic combination of strength, balance, endurance, and flexibility. The following table summarises the key tests, what they measure, and their relevance to daily life.

Key Senior Fitness Tests at a Glance

| Test Name | Fitness Domain Assessed | Real-World Application |

|---|---|---|

| 30-Second Chair Stand | Lower Body Strength | Getting up from a chair, toilet, or out of a car. |

| Arm Curl Test | Upper Body Strength | Carrying groceries, lifting grandchildren, daily chores. |

| Timed Up and Go (TUG) | Mobility & Dynamic Balance | Moving around the house safely, reacting to obstacles. |

| 6-Minute Walk Test | Aerobic Endurance | Shopping, walking through a park, keeping up with friends. |

| Chair Sit-and-Reach | Lower Body Flexibility | Bending to tie shoes, picking objects up off the floor. |

Each test provides a piece of the puzzle, helping to build a complete picture of an individual's functional capacity.

The 30-Second Chair Stand Test

This simple yet informative test measures lower body strength, which is directly linked to the ability to rise from a seated position—a fundamental aspect of independence.

- Equipment: A stopwatch and a sturdy chair without armrests, with a seat height of approximately 44 cm (17 inches).

- Procedure: The individual sits in the middle of the chair with feet flat on the floor, arms crossed over their chest, and back straight. On "go," they rise to a full standing position and then sit back down completely. The score is the total number of repetitions completed in 30 seconds.

- Interpretation: A higher number of repetitions indicates good leg strength and power, which is essential for mobility and reducing fall risk. For similar assessments, you can explore the 5 Times Sit to Stand test in our guide.

The Arm Curl Test

This test assesses upper body strength, which is crucial for lifting, carrying, and pushing activities in daily life.

- Equipment: A chair without armrests, a stopwatch, and a dumbbell (2.2 kg or 5 lbs for women, 3.6 kg or 8 lbs for men).

- Procedure: The person sits on the chair with their back straight, holding the dumbbell in their dominant hand with the palm facing up and the arm extended downwards. On "go," they perform a bicep curl and then lower the weight back to the starting position. The score is the number of full curls completed in 30 seconds.

- Interpretation: This provides a quick measure of arm and shoulder strength, reflecting the ability to handle tasks like carrying groceries or lifting a suitcase.

Timed Up and Go Test

The Timed Up and Go (TUG) is a widely accepted assessment of mobility, balance, and fall risk, timing a sequence of common movements.

- Equipment: A standard chair with armrests, a stopwatch, and a marker placed 3 meters (10 feet) in front of the chair.

- Procedure: The individual starts seated. On "go," they stand up, walk at a comfortable and safe pace to the marker, turn, walk back, and sit down again completely. The time is stopped when they are fully seated.

- Interpretation: The TUG is a strong predictor of functional mobility. A time of 12 seconds or more is often associated with a higher risk of falling and may indicate underlying issues with balance or coordination (1).

A good TUG score reflects not just speed, but how well the neuromuscular system coordinates movement. This translates directly into the confidence needed to move freely in one's home and community.

The 6-Minute Walk Test

This test measures aerobic endurance by assessing how efficiently the cardiovascular and respiratory systems supply oxygen to muscles during sustained activity.

- Equipment: A stopwatch and a clear, flat walking path where distance can be measured.

- Procedure: The objective is to walk as far as possible in 6 minutes without running. The individual may slow down or rest if needed, but the clock continues. The final score is the total distance covered.

- Interpretation: A greater distance walked indicates better cardiovascular fitness, reflecting the stamina needed for activities like shopping, gardening, or walking with family.

The Chair Sit-and-Reach Test

This test assesses lower body flexibility, particularly in the hamstrings and lower back, where tightness can make daily movements difficult.

- Equipment: A chair and a ruler.

- Procedure: The person sits on the edge of the chair with one leg extended straight, heel on the floor, and toes pointing up. The other foot is flat on the floor. With hands stacked, they slowly bend forward from the hip to reach toward their toes.

- Interpretation: The distance reached is measured (relative to the toes). Better flexibility in this area can prevent stiffness and makes bending movements easier.

How to Turn Your Test Results Into Meaningful Insights

Completing fitness tests is the first step; understanding the results is where real value is created. The scores are not a judgment but a functional health dashboard—a data-driven snapshot of physical abilities at a specific moment. Interpreting these results involves turning raw numbers into powerful insights, highlighting strengths and pinpointing areas where focused effort can significantly improve daily life and long-term independence.

Moving Beyond Pass or Fail

It is important to approach results with the right perspective. Scores from tests like the 30-Second Chair Stand or the Timed Up and Go (TUG) are most useful when compared to normative data. This data, derived from large scientific studies, provides a benchmark of typical performance for specific age and gender groups. However, these are guidelines, not rigid pass/fail criteria. A score below the average is not a cause for alarm but a clear signal indicating an area for improvement. This information empowers more productive conversations with a physiotherapist or doctor about setting realistic and motivating goals. For more on this concept, you can learn what normative data is and how it's used.

Think of it like a car's dashboard. A low tire pressure warning isn't a failure—it's a helpful alert that tells you exactly where to direct your attention to keep everything running smoothly and safely.

Using Normative Data as a Guide

Let’s examine sample normative values from peer-reviewed research for the 30-Second Chair Stand Test, a key indicator of lower body strength. The table below presents average repetitions and should be used as a reference point, not a strict target.

Normative Values for the 30-Second Chair Stand Test (Men & Women)

| Age Group | Men (Average Reps) | Women (Average Reps) |

|---|---|---|

| 60-64 | 14 | 12 |

| 65-69 | 12 | 11 |

| 70-74 | 12 | 10 |

| 75-79 | 11 | 10 |

| 80-84 | 10 | 9 |

| 85-89 | 8 | 8 |

| 90-94 | 7 | 4 |

| (Data adapted from studies on functional fitness norms for older adults (6)) |

This data provides context, transforming a simple count into a meaningful piece of the health puzzle.

Translating Numbers into Real-World Meaning

Let’s consider a practical example. A 72-year-old woman completes 8 repetitions on the Chair Stand Test. The table shows the average is 10 for women in her age group. This is not a "bad" score; it is valuable information. It indicates that focusing on lower-body strength exercises, such as squats or leg presses, could be an effective way to improve her ability to rise from chairs and maintain independence. Other test results offer similarly direct insights:

- A Timed Up and Go (TUG) score over 12 seconds: This often flags an increased risk of falling (1). A plan would likely include exercises to improve dynamic balance, walking patterns, and leg strength.

- A low 6-Minute Walk Test distance: This points to a need for better aerobic endurance. The focus would shift to activities like brisk walking, cycling, or swimming.

- A limited Chair Sit-and-Reach score: This highlights tightness in the hamstrings and lower back, suggesting that a consistent stretching routine would be beneficial.

Ultimately, interpreting fitness results is about connecting data to daily function. It shows how a number relates to the ability to live a full, active life, providing a logical and empowering starting point for a fitness journey.

Prioritizing Safety During Any Fitness Assessment

While collecting accurate data is important, the well-being of the individual being tested is paramount. When assessing older adults, safety is the foundation of an effective evaluation. The goal is to build confidence and gather useful information, never to create risk or cause injury. This begins with a thorough pre-screening process to identify any underlying health conditions that might require medical clearance.

Start with Smart Screening

A well-regarded tool for this is the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+). This evidence-based questionnaire helps identify potential red flags, such as recent chest pain, dizziness, or bone and joint issues that could be aggravated by physical activity (7). A "yes" answer to key questions does not preclude testing; rather, it prompts consultation with a doctor or physiotherapist who can provide guidance on which tests are safe and what modifications may be necessary.

Creating a Secure Testing Environment

The next layer of safety is the physical space. A safe environment is a controlled one.

Here are key considerations for the testing area:

- Clear the Area: Ensure the space is free of clutter, loose rugs, electrical cords, or other trip hazards.

- Use Sturdy Equipment: Chairs used for testing must be stable and without wheels, placed on a non-slip surface.

- Provide Plenty of Space: The individual needs enough room to move freely without feeling cramped.

The testing environment should inspire confidence. When an individual feels secure, they can better focus on the task and perform to their ability without apprehension.

The Role of Clear Communication and Supervision

During the assessment, clear communication and supervision are critical. Instructions should be simple and direct, avoiding complex jargon. Demonstrating the movement first helps ensure the person knows what to expect. For dynamic tests like the Timed Up and Go or other balance assessment tests for the elderly, a spotter is essential. The spotter should stand close by to offer support if needed, without interfering with the test. Finally, communication should remain open. The person being tested must feel comfortable stopping immediately if they experience pain, lightheadedness, or significant discomfort. The guiding principle is simple: do no harm. By layering these safety measures, every fitness assessment can be a positive, safe, and insightful experience.

Turning Assessment Results into a Real-World Action Plan

With the assessments complete, the next step is to translate those results into a clear, personalised, and effective action plan. The test scores are starting coordinates on a map, showing the current location. From this point, it is possible to plot the most direct and safest route toward an individual's goals, whether that is better stability, greater strength, or increased endurance.

From Data to Design: A Case Study

Let’s consider a practical example. A 75-year-old woman wants to feel steadier on her feet and have more confidence playing with her grandchildren. Her Timed Up and Go (TUG) test result was 13.5 seconds. Since scores over 12 seconds are often linked to a higher risk of falling, this provides a clear priority (1).

Her other test results add further detail:

- 30-Second Chair Stand: 9 repetitions (Slightly below average for her age, indicating a need to build lower-body strength).

- 6-Minute Walk Test: She covered a respectable distance but reported feeling breathless (Suggesting room for improvement in aerobic capacity).

Building a Personalised Plan

This data allows for the creation of a balanced program targeting three key areas, rather than relying on guesswork.

- Dynamic Balance and Mobility: To improve her TUG score, her plan should include exercises that mimic the test, such as practicing standing up and sitting down without using her hands, and safely walking and turning. Simple drills like tandem walking (heel-to-toe) would also be beneficial.

- Lower-Body Strength: To improve her Chair Stand score, foundational strength work is needed. This could start with modified bodyweight squats and progress to using light resistance bands.

- Aerobic Endurance: To boost her stamina, the plan could start with 10-15 minute walks, three to four times a week, with a gradual increase in duration as her capacity improves.

This approach connects a specific test result to a targeted intervention. It is not exercising for the sake of it; it is training with a clear purpose informed by objective data.

The Power of Regular Re-Testing

This action plan is not static; it should evolve as function improves. Re-testing is a critical part of this process. For most older adults, reassessing every three to six months is an effective strategy. It is frequent enough to detect meaningful changes and allow for adjustments to the exercise program. When a balance exercise becomes too easy, re-test results will reflect this, signaling that it is time for a more challenging variation. This cycle of test, train, and re-test creates a powerful feedback loop. It ensures the program remains effective, maintains motivation by showing tangible progress, and reinforces that fitness testing for seniors is not a one-time event but the start of a continuous journey toward maintaining independence and thriving.

Your Questions About Senior Fitness Testing, Answered

Navigating the world of fitness testing for older adults can seem complex. Here are answers to some of the most common questions.

How Often Should a Senior Get Tested?

As a general guideline, a full fitness assessment every six months is a suitable baseline for most healthy older adults. This frequency allows for tracking changes and adjusting programs without being overly burdensome. This can be modified based on individual circumstances. After a significant health event like an illness, fall, or surgery, testing every three months may be valuable for monitoring recovery (1). Conversely, a very active and stable individual might only need an annual check-in. The assessments serve as a compass to guide the fitness journey.

Can We Do These Fitness Tests at Home?

Yes, many foundational tests, such as the 30-Second Chair Stand, can be performed at home with minimal equipment. However, safety must be the top priority. The space should be cleared of trip hazards, and a sturdy, stable chair without wheels must be used. Whenever possible, a family member or friend should be present to act as a spotter. While performing follow-up tests at home is useful for tracking progress, it is recommended that the initial assessment be conducted with a qualified professional to ensure correct technique and accurate interpretation of results.

What if I Score Below Average on a Test?

A score below the typical range for your age group should not be viewed as a failure. It is simply information—a clear indicator of which area of fitness requires more focus. It presents an opportunity to set a specific, achievable goal.

A lower-than-average score on a test is just a starting point. It provides the precise data needed to build a targeted plan that can lead to significant improvements in physical function at any age.

This kind of result can be highly motivating, providing the data needed to build a truly personalised program that drives meaningful results.

Here at Meloq, we're passionate about using objective data to build safer and more effective training and rehabilitation programs. Our digital measurement tools are designed to give professionals the accurate, repeatable insights they need to guide their clients toward better health and performance. See how our ecosystem can elevate your practice by visiting the official Meloq website.