A Scientific Guide to Dynamic Balancing Equipment in Physiotherapy and Sports Training

Team Meloq

Author

For years, a clinician’s trained eye was the gold standard for assessing balance. We would watch a patient stand, walk, or perform a specific test and make a clinical judgment. While that experience is invaluable, it’s ultimately a qualitative assessment. It tells us if someone is unsteady, but it struggles to quantify how unsteady they are or pinpoint why with objective certainty.

This subjectivity makes it challenging to track subtle, day-to-day improvements in a patient's recovery or spot the small asymmetries that could be red flags for an injury risk, as highlighted in numerous biomechanical studies (1).

Moving Beyond Observation with Dynamic Balancing Equipment

This is where modern dynamic balancing equipment changes the landscape of clinical practice. It represents a fundamental shift from simple observation to precise, objective measurement, giving us a clear window into how an individual's neuromuscular system is performing.

Think of it like a high-performance vehicle's diagnostic system. Instead of just observing how a car handles a turn, you get exact data on suspension response and weight distribution. Dynamic balance tools offer a similar level of granular insight for the human body.

Uncovering the Balance Blueprint

At its core, dynamic balance is the complex process of maintaining stability while in motion or reacting to external perturbations. This process involves a rapid feedback loop between the central nervous system, peripheral nerves, and muscles (2).

The right equipment can capture the minute, often invisible adjustments a person makes to stay upright. To do this, it measures key biomechanical variables, with one of the most foundational being the Center of Pressure (COP).

- What is the Center of Pressure? The COP is the single point representing the sum of all pressures across the surface of the feet in contact with the ground.

- Why does it matter? As you stand or move, your body constantly adjusts your weight, causing the COP to travel. The pattern, speed, and area of this travel—often called postural sway—provide a wealth of information about an individual's underlying stability (2).

From Raw Data to Actionable Insights

By capturing COP data and other key metrics, this technology transforms abstract concepts like "poor balance" into quantifiable data. A therapist can see not just that a patient is favouring one leg after an ankle sprain, but that they are exhibiting a 30% greater medial-lateral sway velocity on the affected side during a specific task.

This level of detail is empowering. To explore the principles behind these measurements, you can learn more about the objective of measurement in our dedicated article.

Ultimately, this data-driven approach removes much of the guesswork from clinical assessment. It allows for highly personalized rehabilitation programmes, more confident return-to-sport decisions, and a better understanding of fall risk in older adults (1,2). It equips professionals with the objective evidence needed to optimize performance and deliver better patient outcomes.

References

- Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Jun;46(2):239-48.

- Paillard T. Plasticity of the postural function to sport and/or balance training. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017 Jan;72:129-52.

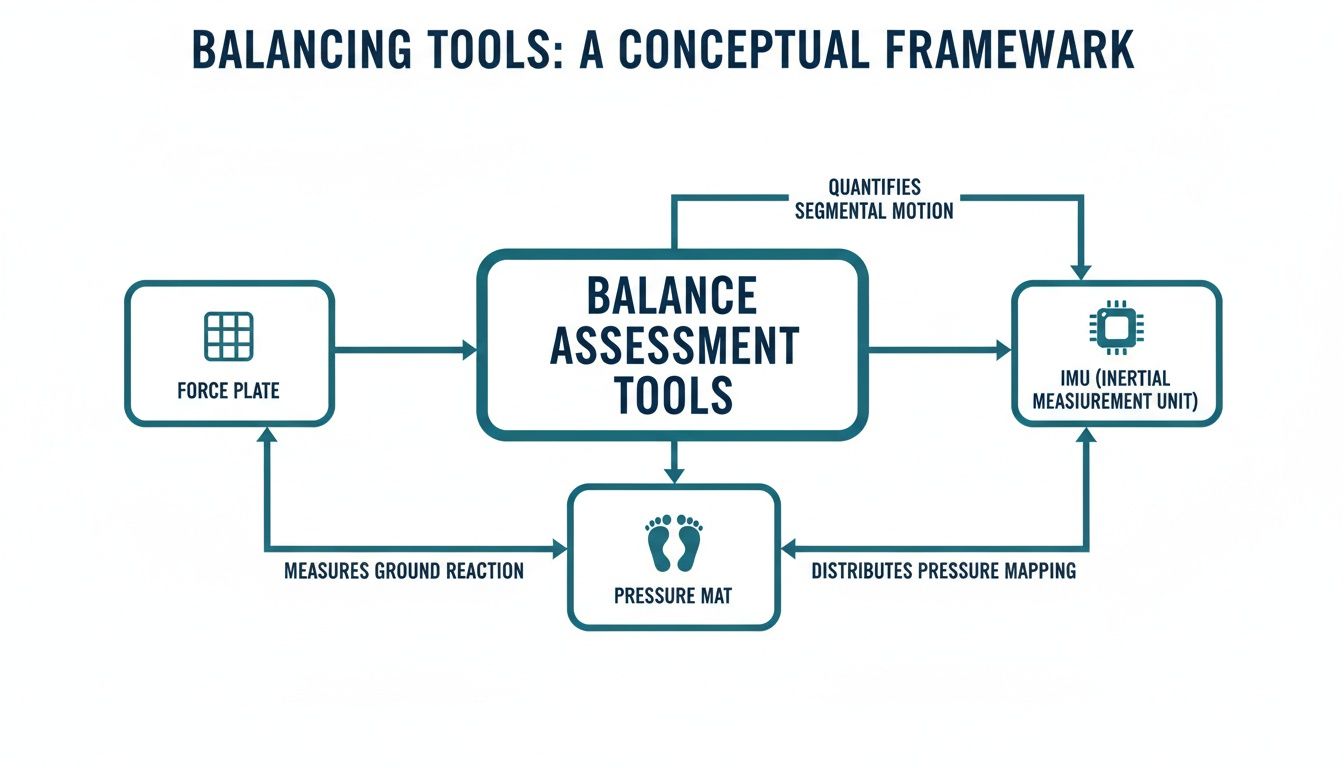

A Comparative Look at Dynamic Balancing Tools

Selecting the appropriate dynamic balancing equipment can feel like choosing from a range of specialized scientific instruments. Each tool provides a unique window into an individual's stability, and understanding their differences is crucial for making an informed decision for your practice or team. Let's break down the most common options available.

Each device operates on a slightly different principle, generating specific data that is valuable in different clinical and performance settings.

Force Plates: The Gold Standard

Force plates are widely considered the gold standard for balance and biomechanical assessment in research settings. They function as highly sensitive, multidirectional scales that measure ground reaction forces. They go far beyond simple weight measurement to detect precisely how forces are distributed and shift in real-time, providing clean Center of Pressure (COP) data.

This high-fidelity data makes them indispensable for detailed gait analysis, jump testing, and identifying subtle asymmetries that are often missed by the naked eye. Their high validity and reliability are well-established in scientific literature, making them a cornerstone of biomechanics research (1). The primary trade-off is that they are typically not portable and represent a significant financial investment, often confining them to dedicated laboratory or large clinical environments.

Dynamic Balance Boards

If a force plate is a precision laboratory instrument, a dynamic balance board is more like an active training tool that also quantifies performance. These devices are typically unstable surfaces—such as instrumented rocker or wobble boards—designed to track an individual's ability to maintain their balance.

Here, the focus is less on microscopic COP shifts and more on quantifying reactive postural control. The equipment measures how effectively someone can correct their position and find stability when the supporting surface is in motion. This makes them a natural fit for rehabilitation, particularly for conditions like chronic ankle instability. Research has shown that training on these devices can enhance sensorimotor function and postural control, serving as both a therapeutic and an assessment tool (2).

Inertial Measurement Units (IMUs)

Inertial Measurement Units, or IMUs, take a completely different approach. These are small, wearable sensors, similar to those found in smartphones, that contain accelerometers and gyroscopes. Placed on the body, they measure the movement, orientation, and gravitational forces of a specific limb or the trunk.

Their primary advantage is portability. An IMU can be used virtually anywhere—in the clinic, on the field, or even at a client's home—to capture balance and movement data in ecologically valid environments.

- Clinical Versatility: They are effective for measuring postural sway during standing, assessing gait stability during locomotion, or analyzing trunk control during a functional task.

- Sport-Specific Application: For athletes, they can deliver on-the-spot data about running form or landing stability directly on the court or field.

This "go-anywhere" capability makes them an excellent tool for assessments outside the clinic, though consistent placement and careful data interpretation are essential to ensure reliability. For a deeper understanding of the force principles these devices measure, our guide on the device to measure force is a useful resource.

Pressure Mats

Pressure mats belong to the same family as force plates but offer a different type of detail. Instead of calculating a single COP point, a pressure mat uses a grid of thousands of sensors to create a high-resolution map of pressure distribution across the entire plantar surface of the feet.

This granular detail is ideal for applications where foot function is the central question. For example, in managing the diabetic foot, it can pinpoint high-pressure areas at risk for ulceration. For runners, it can reveal precisely how the foot loads during each phase of the gait cycle, helping to inform decisions on footwear or injury prevention strategies.

To make sense of these options, it helps to see them side-by-side.

Comparing Key Dynamic Balancing Equipment

This table provides a quick overview of common tools, highlighting their primary measurements, key advantages, and typical applications.

| Equipment Type | Primary Measurement | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Plate | Center of Pressure (COP), Ground Reaction Forces | High accuracy, Gold-standard for research | Gait analysis, Jump testing, Post-injury assessment |

| Balance Board | Reactive postural control, Time to stabilization | Combines assessment with training, Engaging for patients | Ankle instability rehab, Proprioceptive training |

| IMU Sensor | Body segment orientation, Acceleration, Velocity | Highly portable, Captures real-world movement | Field-based testing, Remote monitoring, Gait analysis |

| Pressure Mat | Detailed pressure distribution across the foot | High-resolution foot data, Identifies pressure hotspots | Diabetic foot assessment, Orthotic design, Running analysis |

Ultimately, the best dynamic balancing equipment is not about which tool is superior overall, but which one is the most appropriate for your specific needs, your client population, and the scientific questions you aim to answer.

References

- Ruhe A, Fejer R, Walker B. The test-retest reliability of centre of pressure measures in bipedal static task conditions - a systematic review of the literature. Gait Posture. 2010 Nov;32(4):436-45.

- Hale SA, Fergus A, Axmacher R, Kiser K. The effects of a 4-week wobble board and elastic resistance band training program on static balance. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Apr;9(2):199-209.

How These Devices Actually Measure Balance

To fully appreciate what dynamic balancing equipment offers, we need to understand how it works. These tools go beyond visual observation, translating the body's subtle, often invisible movements into hard, objective data. This process relies on a few core biomechanical principles that reveal the true nature of an individual's balance.

At the heart of balance measurement is a metric called the Center of Pressure (COP). The COP represents the body’s exact balance point on the ground at any given millisecond. It is the single point where the sum of all ground reaction forces acts on the support surface.

Even when you are standing as still as possible, your body is never truly motionless. You are constantly making tiny, subconscious muscle adjustments to maintain an upright posture. These small corrections cause your COP to wander within a small area. This movement is known as postural sway, and this equipment is engineered to capture and quantify that sway with remarkable precision.

From Static Stance to Dynamic Action

Balance is not a singular concept. It is generally broken down into two main categories, each providing a different piece of the clinical puzzle.

- Static Balance: This refers to stability while standing still, often under different conditions such as with eyes open or closed. It provides a baseline for a person's postural control when there are minimal external challenges.

- Dynamic Balance: This is where the assessment becomes more functionally relevant. It concerns stability during movement—such as an athlete landing from a jump or a patient stepping over an obstacle. This is often far more revealing as it tests the body's ability to react and regain control in real-time.

A growing body of scientific evidence suggests that dynamic tasks are often better predictors of outcomes like fall risk or an athlete's readiness to return to sport, simply because they more closely mimic the challenges of the real world (1).

This is a look at the main types of tools we use to capture these balance metrics.

Each of these devices, from force plates to wearable IMUs, provides a unique window into the critical data points that define an individual's balance.

What Do the Numbers Actually Mean?

This equipment generates specific metrics that have real clinical significance. It is also important to remember that foot mechanics play a crucial role. For a primer on this topic, this guide on understanding pronation and supination is a valuable resource, as these movements significantly impact stability.

Here are a few of the key metrics you will encounter and what they may indicate, presented with caution as interpretation requires clinical context:

- Sway Area: This is the total area the COP covers during a trial. A larger sway area might suggest that a person's neuromuscular system is working harder, causing them to "search" over a wider area to maintain stability.

- Sway Velocity: This metric tells you how fast the COP is moving. A higher velocity can indicate that the body is making more frequent or larger adjustments to stay balanced.

- Medial-Lateral and Anterior-Posterior Sway: This breaks down the sway into side-to-side and front-to-back components. A significant asymmetry in these values could point to a unilateral weakness, possibly resulting from an injury like an ACL tear or a neurological event like a stroke.

This is how we bridge the gap between observation and physiology. A therapist can move from stating a patient "looks unsteady" to reporting, "Their medial-lateral sway velocity has decreased by 25% following the intervention, as measured during a single-leg stance."

This quantitative approach allows us to track progress with precision, pinpoint specific deficits, and ultimately make more confident, evidence-informed decisions about a person's care or training plan. For a deeper dive, explore our article on the Center of Pressure.

References

- Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Jun;46(2):239-48.

Putting Balance Data into Clinical Practice

Understanding the numbers behind balance is one thing, but translating that data into tangible patient outcomes is where dynamic balancing equipment truly proves its value. When we move from theory to practice, objective data empowers clinicians and coaches to build specific, effective, and evidence-based plans for a diverse range of individuals.

The adoption of these tools is on the rise as more clinics integrate them into daily workflows. The global market for this technology is expanding, with projections showing significant growth in the coming years. You can explore the full market outlook to get a deeper sense of this trend.

Let's examine some real-world applications in sports physiotherapy, neurological rehabilitation, and geriatric care to see how these devices are leading to smarter clinical decisions and better patient progress.

Sports Physiotherapy and Return to Play

In sports rehabilitation, the stakes are high. Clearing an athlete to return to play is a critical decision. Dynamic balancing equipment helps to remove subjectivity from this judgment call, supporting clinical expertise with objective data.

A significant challenge after an ACL reconstruction is the persistence of neuromuscular deficits, even when strength and range of motion appear to have returned to normal. An athlete might feel ready, but hidden asymmetries in landing mechanics can substantially increase their risk of re-injury (1).

A force plate can identify these asymmetries with high precision. By having an athlete perform a series of drop jumps, a physiotherapist can objectively measure variables such as:

- Landing Symmetry: Is the athlete absorbing force evenly between the surgically repaired limb and the uninjured one? A significant imbalance is a red flag for a compensatory pattern that needs to be addressed.

- Time to Stabilization: How quickly can they control their landing and regain stability? A longer time may point to deficits in neuromuscular control.

- Vertical Ground Reaction Force: Are they generating and absorbing power appropriately for their sport? This data informs whether they are truly ready for game-day demands.

Armed with this information, a therapist can confidently state, "Your left leg is still absorbing 20% less force upon landing. We need to focus on these specific plyometric drills before you return to full practice."

Neurological Rehabilitation and Motor Control

For patients recovering from a stroke or managing a condition like Parkinson's disease, balance is fundamental to their functional independence. Dynamic balancing equipment provides a powerful way to track improvements in motor control and refine interventions.

Consider a patient with Parkinson's disease, who often experiences postural instability. A dynamic balance board can be used for regular assessments to track changes in their sway velocity and area. Seeing these numbers decrease over time is not just encouraging; it is objective evidence that the exercise programme is improving their postural control.

A similar principle applies in post-stroke rehabilitation. Measuring medial-lateral sway can instantly highlight a patient's difficulty in shifting weight onto their affected side. This data allows for the design of targeted drills, such as specific weight-shifting exercises, and the same equipment can then be used to measure the direct impact of the intervention on their stability.

Geriatric Care and Fall Prevention

Falls among older adults represent a significant public health issue. Accurately identifying those at high risk is a priority for any clinician in this field. While traditional tests like the Timed Up and Go are valuable, dynamic balancing equipment adds a deeper layer of insight into why an individual might be unstable.

Research has shown that certain metrics from dynamic balance tests—such as an increase in postural sway during dual-task conditions (e.g., standing still while counting backwards)—are strong predictors of future falls (2).

- Baseline Assessment: A brief static and dynamic balance test can provide a baseline fall risk profile for a new patient.

- Intervention Efficacy: Following a balance training programme, a follow-up assessment provides objective data to show whether the intervention has successfully reduced their sway and, by extension, their risk of falling.

By incorporating this technology into practice, we can move beyond generic fall prevention advice and create truly personalized programmes based on an individual's specific balance deficits, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful outcomes.

References

- Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, et al. Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Oct;38(10):1968-78.

- Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Jun;46(2):239-48.

Choosing the Right Equipment for Your Practice

Integrating new technology into a clinic or performance centre is a significant decision. When it comes to dynamic balancing equipment, the right choice is not just about the price—it is about investing in a tool that genuinely improves patient care and provides sharper insights. The goal is to find equipment that fits your budget, workflow, and the unique needs of the people you work with every day.

The first step is to carefully consider your primary patient population. Are you helping older adults reduce their fall risk? Guiding athletes through return-to-play decisions? A neurological rehabilitation clinic will have different needs than a high-performance sports facility. Knowing your primary focus is crucial.

Aligning Technology with Clinical Needs

Before examining specific devices, map out what you need to measure. Is your focus on ACL recovery, baseline concussion testing, or geriatric fall prevention? Your answer will point you toward the most appropriate technology.

For instance, a force plate delivers high accuracy for jump testing and identifying subtle landing asymmetries—perfect for a sports-focused practice. However, if you conduct assessments on the field, the portability of wearable IMU sensors might be the most important factor.

It is key to avoid the temptation of purchasing a device for features you might use in the future. Focus on what solves the problems you face now. The best equipment is the one that is used consistently because it delivers clear, actionable data for your clients.

The Importance of Scientific Validation

In an evidence-based practice, your data is only as good as the tool that collects it. It is essential to choose equipment with a strong track record of validity (does it measure what it claims to measure?) and reliability (does it provide consistent results?). A good starting point is to look for devices that have been used in peer-reviewed scientific studies.

A manufacturer should be transparent about the research supporting their product. When you choose a tool backed by science, you can be confident that the metrics you are collecting are trustworthy enough to base clinical decisions upon (1).

Practical Considerations for Implementation

Beyond the technical specifications, a few practical factors will determine how well a new device integrates into your practice. A tool that is difficult to use will likely be underutilized.

Consider these key factors:

- Software Usability: How intuitive is the software? Can your team be trained quickly to run tests and interpret reports?

- Portability and Setup: If you work in multiple locations, portability is essential. How long does it take to set up and calibrate the device before use?

- Integration with Workflow: How easily can a balance test be incorporated into a standard appointment? A test that takes 20 minutes is impractical in a busy clinic. Look for protocols that are efficient enough for both baseline assessments and progress checks. For a deeper dive into the mechanics, check out our guide on force platforms in biomechanics.

Budget and Return on Investment

Finally, there is the budget. Dynamic balancing equipment can range from a few thousand dollars for simpler systems to tens of thousands for high-end force plates. It is helpful to view this as an investment in your practice's capabilities, not just an expense.

While cost is always a factor, it is interesting to note the value placed on such precision in other fields. For example, in the specialized world of turbocharger dynamic balancing machines, the market was valued at USD 178 million in 2025 and is projected to climb to USD 275 million by 2034. You can discover more insights about these market trends to see just how critical this technology is across industries.

For your own practice, having a clear plan for how the equipment will improve your services or attract new clients can make the initial investment much easier to justify. By carefully weighing your clinical needs, the scientific evidence, everyday usability, and your budget, you can find the dynamic balancing tool that will elevate your standard of care and set your practice apart.

References

- Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Jun;46(2):239-48.

Your Questions About Dynamic Balancing Equipment, Answered

As objective data becomes the standard in modern practice, it is natural for clinicians and coaches to have questions about incorporating dynamic balancing equipment into their workflow. Let's address some of the most common inquiries to provide a clear, practical understanding of this technology.

What’s the Real Difference Between Static and Dynamic Balance Tests?

Think of static balance as holding a stationary pose—like standing on one leg with your eyes closed. It provides a baseline for postural control under predictable conditions.

Dynamic balance, on the other hand, is about maintaining stability while in motion. This could involve landing from a jump, performing a squat, or reacting to an unstable surface. It is balance in action.

For most clinical and field-based applications, dynamic tests are often more revealing. They tend to better mimic the demands of daily life and sport. In fact, scientific literature consistently suggests that deficits in dynamic balance can be stronger predictors of injury risk and falls than static measures alone (1).

How Much Time Does a Balance Assessment Actually Take?

This is a critical question for any busy clinic, and the answer is often "less time than you might think." Modern dynamic balancing equipment is designed for efficiency. A standard balance test, whether static or dynamic, can frequently be completed within a few minutes.

A common protocol, for example, might involve three 30-second trials on a force plate. Including patient instructions and brief rests, the entire assessment can fit comfortably into a typical appointment slot. This makes it practical for everything from initial evaluations to regular progress checks.

Is This Kind of Equipment Only for Elite Athletes?

While you will certainly find dynamic balance tools in high-performance sports settings, their application is much broader. The same principles used to assess an athlete's landing symmetry after an ACL repair are incredibly useful for other populations.

- Neurological Rehabilitation: It can be used to track the subtle recovery of motor control in a post-stroke or Parkinson's patient.

- Geriatric Care: You can objectively measure fall risk in older adults and assess the efficacy of balance interventions.

- General Physiotherapy: It is ideal for investigating the root cause of stability issues in patients with chronic low back pain or recurrent ankle sprains.

The key takeaway is that if stability and neuromuscular control are part of the clinical picture, this objective data can be beneficial. The equipment provides a precise window into an individual's functional ability, regardless of their activity level.

How Is This Different from a Balance App on My Phone?

Many mobile apps use a smartphone's built-in accelerometer to estimate a person's sway. While convenient, they offer a very limited and often unvalidated snapshot.

Professional dynamic balancing equipment—like a force plate or dedicated IMUs—is in a completely different class in terms of accuracy and reliability. These clinical-grade tools have undergone rigorous scientific testing to validate that their measurements are precise enough to guide treatment decisions. An app might be a useful tool for a basic screen or to promote patient engagement, but it typically lacks the validated precision required for clinical diagnostics or for tracking small but meaningful changes over time (2).

Is This Technology a Smart Investment for My Practice?

Any new equipment purchase requires a careful analysis of the value it brings. Dynamic balancing equipment provides objective, quantifiable data that can elevate your standard of care, support your clinical decisions with evidence, and improve communication with patients.

This drive for precision is not unique to healthcare. The broader market for balancing machines—used in everything from industrial rotors to crankshafts—has seen significant growth, expanding from USD 94 million in 2019 to a projected USD 3.24 billion by 2032. You can see these industrial market trends for yourself to appreciate the value placed on this technology across sectors.

For a clinic or training facility, the return on investment is not just financial. It comes from achieving better outcomes, building professional credibility, and being able to offer an elite level of assessment and care.

References

- Hrysomallis C. Relationship between balance ability, training and sports injury risk. Sports Med. 2007;37(6):547-56.

- Mancini M, Horak FB. The relevance of clinical balance assessment tools to differentiate balance deficits. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med. 2010 Jun;46(2):239-48.

Ready to replace subjective guesswork with objective data? The Meloq ecosystem of portable, accurate measurement tools—including our EasyForce dynamometer and EasyBase force plate—is designed to give you the clear, reliable insights you need to optimize patient outcomes.