A Clinician's Guide to Choosing a Device to Measure Force

Team Meloq

Author

A device to measure force is simply a tool built to quantify the push, pull, or torque a person generates. In clinical and sports performance settings, instruments like handheld dynamometers, force plates, and load cells translate physical effort into objective data, moving assessment beyond subjective guesswork.

Moving From Subjective Art to Objective Science

For decades, assessing a patient's strength was often more of an art than a science. Clinicians relied on manual muscle testing (MMT), using their own hands to gauge effort and assign a grade on an ordinal scale (e.g., 0 to 5). While a foundational clinical skill, the method is inherently subjective and can suffer from poor inter-rater reliability, especially in stronger individuals (1). One clinician's "strong" might be another's "moderately strong."

This ambiguity creates practical challenges. How can you be certain a patient has regained sufficient strength? How do you confidently make a return-to-sport decision when data is based on feel? The move toward objective measurement with a dedicated device to measure force answers these critical questions.

The Need for Numbers

Imagine telling an athlete they're "getting stronger." Now, imagine showing them their peak force output has increased from 250 Newtons to 300 Newtons in three weeks. The second statement is precise, motivating, and clinically defensible. A device to measure force delivers that clarity, turning vague observations into actionable data.

This shift is crucial for several key reasons:

- Pinpoint Accuracy: Objective data helps identify specific deficits and asymmetries that subjective tests can easily miss.

- Trackable Progress: Hard numbers allow for clear progress reports, giving patients tangible proof that their rehabilitation is effective.

- Confident Decisions: Quantified metrics are the bedrock of realistic goal-setting and evidence-based decisions about rehabilitation milestones.

The use of quantified force measurement demonstrably improves clinical decision-making. Historically, manual muscle testing on a 0–5 scale lacked the sensitivity to detect small but clinically important strength changes (1).

Modern digital dynamometers and force plates can detect strength changes often below 10%—a nuance that can be missed by older ordinal scales. This precision is why many return-to-sport protocols now use limb symmetry differences of less than 10%–15% as key thresholds for safe progression, a standard born from extensive sports science research (2).

By embracing objective measurement, clinicians can elevate their standard of care. This guide will explore the primary devices available—from force plates to dynamometers—providing a practical roadmap for choosing and implementing the right tools. A great place to start is by understanding the fundamentals of what is outcome measurement.

References

- Bohannon RW. Manual muscle testing: does it meet the standards of an adequate measurement system? Physiother Theory Pract. 2005;21(2):117-21.

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804-8.

How Force Measurement Devices Actually Work

At its core, every modern device to measure force is a translator. It takes a raw, physical action—a patient pushing, an athlete jumping—and converts that mechanical energy into a precise digital number. This process relies on a key component called a transducer.

A transducer is a device that converts one form of energy into another. In force measurement, the most common type of transducer is a load cell. The load cell is the sensitive component of the system that physically detects the push or pull, initiating the measurement process.

The secret to how a load cell "feels" this force often lies in a tiny but crucial component called the strain gauge.

The Role of the Strain Gauge

A strain gauge is essentially a very fine, flexible electrical conductor arranged in a tight, serpentine pattern and bonded to a surface that deforms slightly under pressure.

When force is applied, the surface it’s attached to deforms, and the delicate conductor pattern stretches or compresses along with it. This physical deformation is the key. As the conductor's length and cross-sectional area change, its electrical resistance changes in a highly predictable way. The device sends a small electrical current through the gauge and measures any change in resistance.

- No Force: The current flows with a steady, baseline resistance.

- Force Applied: The conductor stretches or compresses, its resistance changes, and the device detects this change.

- Force Removed: The material returns to its original shape, and the resistance reverts to its baseline.

This minute change in the electrical signal is then amplified, processed, and converted into a digital value we can read, usually in Newtons (N) or pounds of force (lbf). Because the relationship between physical strain and electrical resistance is so consistent, strain gauges provide an exceptionally reliable way to quantify force.

Another Key Player: Piezoelectric Sensors

While strain gauge-based load cells are the workhorses of the industry, some devices use a different principle based on the piezoelectric effect. This phenomenon occurs in certain crystalline materials, like quartz. When mechanical pressure is applied to these crystals, they generate a tiny, measurable electrical charge.

The piezoelectric effect is a direct conversion of mechanical stress into an electrical signal. The amount of charge produced is directly proportional to the amount of force applied, making it well-suited for dynamic measurements, like the rapid impact of a foot strike on a force plate (1).

This method is particularly effective for measuring rapid, dynamic changes in force. That’s why you’ll often find piezoelectric sensors in high-end force platforms used for jump, gait, and impact analysis. The crystal's instantaneous electrical response allows the device to capture fast-moving events with incredible fidelity.

If you want to dive deeper into the mechanics of these tools, you can explore how a dynamometer works. Understanding these fundamental principles helps clinicians become more discerning consumers of technology, better equipped to appreciate the science that brings objectivity to their assessments.

References

- Kistler Group. Piezoelectric effect. Available from: https://www.kistler.com/en/glossary/piezoelectric-effect/

A Brief History of Measuring Force

To fully appreciate the precision available today, it helps to glance back at where it all started. The first attempts to measure force were beautifully simple and purely mechanical, relying on balances and springs. An old-fashioned spring scale was a clever but basic device to measure force that served its purpose for centuries in marketplaces and early engineering workshops.

The industrial revolution created a need for more reliable and standardized ways to quantify force. Building bridges, railways, and machinery required more than "sort of" measurements. This demand pushed innovation beyond simple levers and springs, initiating the shift toward quantitative tools.

From Springs to Sensors: The Electronic Leap

The true game-changer was the transition from mechanical systems to electronic transducers. This marked the move from observing a physical spring stretch to reading a precise signal from an electronic component. It redefined what was possible, paving the way for the accuracy and portability that clinicians now rely on every day.

It took roughly two centuries to progress from simple balance-based methods to the instrumented electronic tools we use today. Standardization efforts began in the U.S. in the 1830s to resolve regional differences. As industry expanded, so did the demand for accurate force measurement. One historical account notes that in the 1910s, a staggering 75–80% of railroad scales were found to be inaccurate, sparking nationwide calibration programs (1). The 20th century introduced electrical standards, with significant acceleration after 1960 due to the rise of load cells and strain-gauge transducers. This evolution ultimately led to the portable digital devices in our clinics today. You can take a deeper dive into the history of force measurement here.

It's worth considering that the engineering challenges of industrial applications—like ensuring a massive railroad scale was accurate—directly contributed to the compact, reliable technology that can now measure an athlete's peak power with pinpoint precision.

This journey from simple springs to sophisticated sensors provides a rich backstory to our modern clinical tools. Each development built upon the last, culminating in devices that are transforming rehabilitation and sports science by providing objective, truly actionable data.

References

- Cooper Instruments & Systems. History of Force Measurement. Available from: https://www.cooperinstruments.com/history-of-force-measurement/

The Top Devices for Measuring Force: A Clinician's Comparison

Picking the right device to measure force is a clinical decision that shapes the quality of the data collected and the insights gained. Several key options are available, each with distinct strengths, and it’s crucial to know which tool fits which job.

This guide will walk through the three main types of devices you'll encounter in a modern clinical or performance setting: force plates, handheld dynamometers, and the versatile load cells. We’ll break down how they work and where they excel, helping you make an informed choice for your practice.

Each device captures force differently, leading to unique workflows, data outputs, and price points. A force plate is ideal for complex, dynamic movements, while a dynamometer is perfect for isolating a specific muscle group.

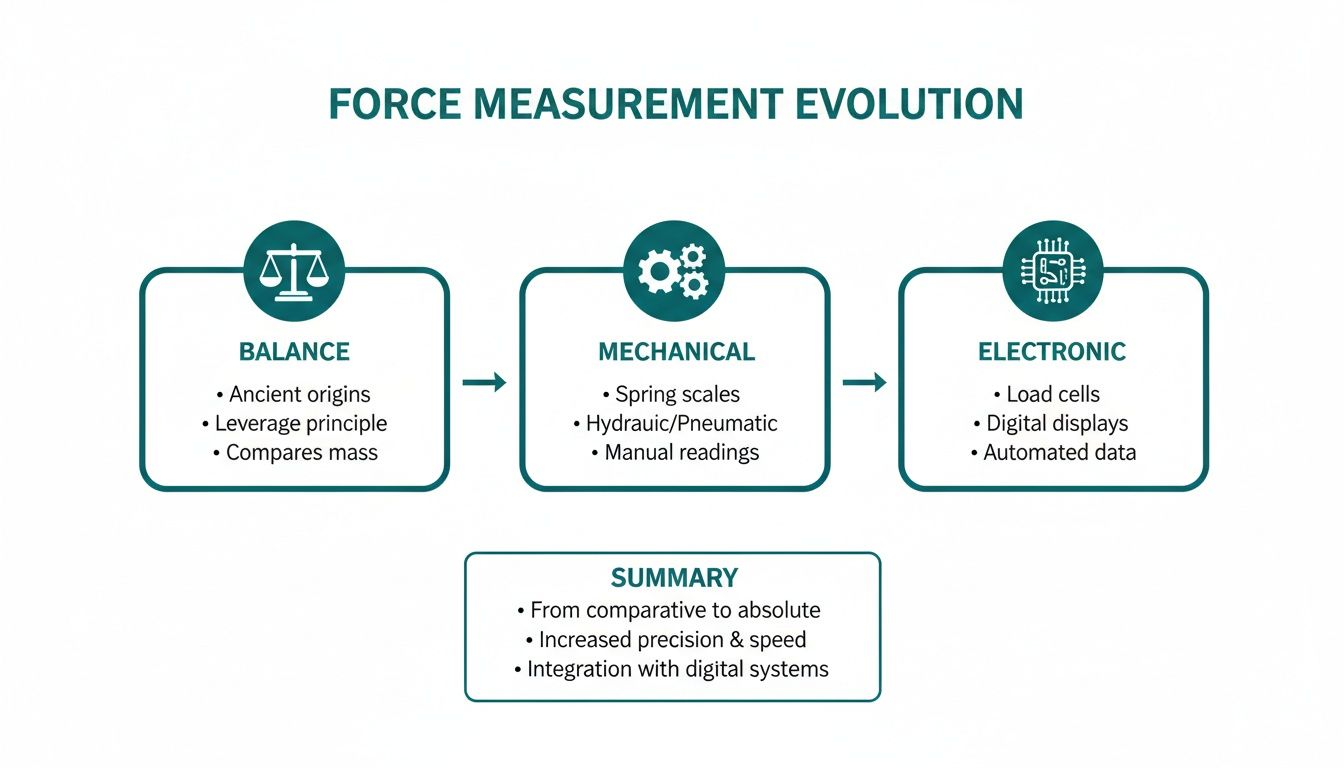

The technology has evolved significantly. The infographic below illustrates the progression from simple mechanical tools to the incredibly precise electronic systems we rely on today.

This visual journey highlights the shift from basic scales to intricate mechanical systems and, finally, to the sophisticated sensors that power modern force measurement. To help you navigate these options, here's a side-by-side look at the main devices used in clinical and sports settings.

Clinical Force Measurement Device Comparison

| Device Type | Primary Use Case | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Force Plates | Analyzing ground reaction forces during dynamic movements like jumps, landings, and gait. | Unmatched detail on force production (e.g., RFD, peak force), balance (CoP), and limb asymmetries. | Traditionally expensive and fixed in place, requiring dedicated lab space. Portable options are becoming more common. |

| Handheld Dynamometers | Measuring isolated muscle strength for specific muscle groups. | Portable, affordable, and easy to use. Provides objective, repeatable data over manual testing. | Accuracy can depend on the clinician's ability to provide stable counter-pressure, especially with strong individuals. |

| Load Cells / Strain Gauges | Custom strength testing setups for specific movements (e.g., isometric pulls, grip strength). | Highly versatile and adaptable. Can be integrated into custom rigs for nearly any test. | Requires more setup and technical knowledge to create a valid and reliable testing system. |

This table provides a high-level overview. The real value comes from understanding the nuances of each tool and how they fit into your clinical workflow.

Force Plates: The Gold Standard for Dynamic Movement

For analyzing how an individual interacts with the ground, force plates are the undisputed gold standard in biomechanics. These rigid platforms contain sensors that measure forces in three dimensions: vertical (up-down), anterior-posterior (forward-backward), and medial-lateral (side-to-side).

When an athlete jumps or a patient walks across the plate, it captures a wealth of data. It’s not just about how much force they produce, but how they produce it over time. This allows for analysis of advanced metrics like rate of force development (RFD) and tracking of their center of pressure (CoP) to assess balance.

Common Clinical and Sports Applications:

- Jump Testing: Analyzing a countermovement jump (CMJ) can reveal information about an athlete's explosive power, identify subtle limb asymmetries, and track neuromuscular fatigue (1).

- Balance and Stability Assessment: By tracking small shifts in a person's center of pressure, force plates provide objective data on postural sway. This is valuable for applications ranging from concussion baseline testing to fall-risk assessments in older adults (2).

- Gait Analysis: A series of force plates can map ground reaction forces during walking or running, offering deep insights into gait mechanics.

Traditionally, force plates have been bulky, expensive, and permanently installed, confining them to university and research labs. However, the emergence of portable force plates is making this high-fidelity data more accessible to clinicians. For a deeper dive, check out this guide to force platforms in biomechanics.

Handheld Dynamometers: Precision for Isolated Strength

While force plates analyze whole-body movements, handheld dynamometers (HHDs) are designed for isolating and quantifying the strength of specific muscle groups.

The process typically involves the clinician pressing the dynamometer against a patient's limb as they exert maximal effort. The device provides an objective reading in Newtons or pounds, removing the guesswork associated with manual muscle testing (MMT).

Instead of a subjective "4/5" grade, you get a precise number—for instance, 225 Newtons. This makes it easy to track progress and identify even minor changes over time. Their portability has made them a staple in physiotherapy clinics and athletic training rooms.

A significant advantage of HHDs is their ability to establish reliable baseline strength data and identify subtle muscle imbalances. Research has shown that limb symmetry data from HHDs is a key metric for guiding return-to-play decisions after injuries like an ACL reconstruction (3).

Pros and Cons of Handheld Dynamometers:

- Advantages: They are portable, relatively inexpensive, and can be used to test almost any muscle group with a consistent protocol. The instant, objective feedback is also beneficial for patient motivation.

- Limitations: The validity of the test can be influenced by the tester. For very strong individuals, the clinician's ability to provide sufficient counter-pressure may become a limiting factor, potentially affecting the results (4). Proper positioning and stabilization are essential.

Load Cells: The Versatile Building Blocks

Load cells are the foundational sensors of force measurement. They are the transducers that reside inside most other force-measuring devices, but they can also be used independently. A load cell is a device that converts a physical force into a measurable electrical signal.

Their versatility is their main strength. In a clinical or performance setting, a load cell might be integrated into a custom testing rig—attached to a cable machine to measure pulling force, mounted in a rack for an isometric mid-thigh pull, or used to build a custom grip strength device.

This adaptability allows practitioners to create objective testing solutions for unique scenarios that off-the-shelf devices may not accommodate.

Ultimately, the best device to measure force depends on your clinical context—your goals, your patients, and your budget. Force plates offer unparalleled detail for dynamic, whole-body movements. Handheld dynamometers deliver portable, precise data on isolated muscles. And load cells provide the ultimate flexibility for custom testing. Many high-performance facilities use a combination of these tools to create a comprehensive picture of an individual's physical capabilities.

References

- McMahon JJ, Suchomel TJ, Lake JP, Comfort P. Understanding the Key Phases of the Countermovement Jump Force-Time Curve. Strength Cond J. 2018;40(4):56-66.

- Gribble PA, Hertel J. Effect of lower-extremity muscle fatigue on postural control. Sports Med. 2003;33(8):601-6.

- Balsalobre-Fernández C, Muñoz-López M, Marchante D, et al. The validity and reliability of a novel app for the measurement of the hamstring eccentric strength. J Sports Sci. 2019;37(4):423-428.

- Stratford P, Balsor B. A comparison of make and break tests using a hand-held dynamometer and the tracking stabilizer. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;19(1):28-32.

Integrating Force Measurement Into Your Practice

Bringing a device to measure force into your clinic is a significant step toward objective, data-driven practice. However, simply owning the tool is not enough. To truly integrate it, you must be able to trust the numbers it provides.

This trust is built on two foundational principles: validation and calibration. Without them, you are merely collecting numbers that lack the scientific rigor required for confident clinical decision-making. Validation confirms that a device accurately measures what it claims to measure, while calibration ensures its accuracy against a known standard.

The Importance of Calibration and Standardized Protocols

Think of calibration as tuning a musical instrument. An uncalibrated device might provide a reading, but it could be consistently inaccurate. When your data is guiding return-to-sport decisions or being used for medico-legal documentation, "close enough" is not sufficient.

Certified calibration provides documentation that your device is accurate. It offers peace of mind that the 300 Newtons of force you measured is a true reflection of your patient’s output, not an instrumental error.

Once you trust your tool, you need to trust your process. This is where standardized testing protocols are essential for achieving consistent, reliable results, especially when multiple clinicians are involved.

A common point of discussion in dynamometry is the difference between a 'make' test and a 'break' test. A 'make' test measures the patient's maximal voluntary isometric contraction against a fixed device. A 'break' test measures the force required for the clinician to overcome the patient’s resistance. Adhering to one method consistently is crucial for reliable longitudinal tracking.

For a great walkthrough, check out our guide on how to use a dynamometer for practical, step-by-step instructions. Standardization minimizes variability, ensuring that observed changes in data are due to the patient, not the testing procedure.

Translating Data Into Clinical Meaning

Data collection is only half the task. Interpretation is where clinical expertise is paramount. A force measurement device can generate numerous metrics, but understanding their clinical significance is what leads to better patient outcomes.

Here are a few key metrics and their interpretations:

- Peak Force: The absolute maximum force a patient produces during a contraction. It’s a simple, powerful indicator of a muscle's maximal strength and is ideal for tracking progress.

- Rate of Force Development (RFD): This metric indicates how quickly an individual can generate force. RFD is critical in sports performance, as it is closely related to explosive power required for actions like jumping, sprinting, and changing direction (1).

- Limb Symmetry Index (LSI): A simple but vital calculation comparing the performance of an injured limb to the contralateral, uninjured limb. It's a common metric for guiding rehabilitation and return-to-play decisions. An LSI below 90% is often considered a clinical threshold indicating that further rehabilitation is needed (2).

As clinicians, we constantly seek ways to incorporate objective data. For an interesting perspective on how another field integrates technology, The Ultimate Cardiologist’s Guide to the Smartwatch ECG offers insights into the use of consumer wearable tech in a medical context.

Streamlining Your Clinical Workflow

The final piece of the puzzle is making force measurement a seamless part of your daily routine. If the process is cumbersome, it is less likely to be used consistently. Modern devices are often designed to reduce administrative burden through app connectivity and potential electronic medical record (EMR) integration.

Imagine finishing a strength test, and the data instantly syncs to an app. With a few taps, you can generate a visual report showing your patient exactly how much they've improved since their last visit. This not only saves documentation time but also serves as a powerful tool for patient engagement. When patients can see their strength improving, their motivation and adherence to the rehabilitation program can increase significantly.

References

- Maffiuletti NA, Aagaard P, Blazevich AJ, Folland J, Tillin N, Duchateau J. Rate of force development: physiological and methodological considerations. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016;116(6):1091-116.

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50(13):804-8.

Where Do We Go From Here? The Future of Quantified Rehab

Bringing a force measurement device into your clinic is more than just an equipment upgrade; it represents a fundamental shift in the approach to patient care.

When we move beyond subjective assessments and begin capturing objective data, we empower ourselves to make better clinical decisions, improve patient buy-in, and create more robust documentation. The conversation changes from a vague "it feels stronger" to a concrete "your peak force output has increased by 15%."

This is how we bridge the gap between the "art" and "science" of rehabilitation. Data tells a clear story, showing progress, uncovering hidden deficits, and ultimately building a stronger foundation of trust with patients. Quantifying force is especially critical for certain populations. For example, clinicians are constantly exploring ways of optimizing strength training for older adults, where objective data is key to managing training load and ensuring safety (1).

What's on the Horizon for Force Measurement?

This field is moving quickly, but two major trends are shaping the future:

- Wearable Sensors: Imagine small, unobtrusive sensors integrated into clothing or worn on the body. These could provide a continuous stream of force and movement data from a patient's daily life, offering a 24/7 perspective on their functional capacity outside the clinic.

- Integrated Biometrics: The next breakthrough will likely involve combining force data with other physiological markers like heart rate variability, muscle oxygenation (SmO2), and sleep quality. This holistic approach could create a more complete picture of an athlete's readiness, stress, and recovery status.

Ultimately, this is about empowerment. By confidently incorporating these tools into practice, clinicians can elevate their standard of care, drive better, more measurable outcomes, and quantify the rehabilitation journey for every client.

The future is not about data replacing clinical intuition, but rather augmenting it with objective evidence. Embracing these tools allows practitioners to lead a new era of quantified, evidence-based practice where every decision is supported by objective reality.

References

- Fragala MS, Cadore EL, Dorgo S, et al. Resistance Training for Older Adults: Position Statement From the National Strength and Conditioning Association. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;33(8):2019-2052.

Got Questions? We Have Answers.

Adopting objective measurement tools naturally brings up practical questions. When determining which force measurement device is right for your clinic, you need clear, straightforward answers. Let's address some of the most common questions from clinicians and performance specialists.

Our goal is to provide concise, real-world insights so you can confidently integrate these powerful tools into your practice and obtain reliable, actionable data.

How Often Should My Device Be Calibrated?

Calibration is the process that ensures your data is trustworthy. The ideal frequency depends on the manufacturer's recommendations, your clinical standards, and usage frequency. For most clinical-grade devices like dynamometers and force plates, annual calibration by an accredited laboratory is considered the standard.

This is not just good practice; it ensures the device performs to its stated accuracy, providing data that is both clinically reliable and legally defensible. If a device is dropped or subjected to heavy, constant use, more frequent calibration checks may be advisable.

What's the Difference Between a 'Make' Test and a 'Break' Test?

These are the two primary methods for using a handheld dynamometer. For data consistency, it is critical to choose one method and use it for all subsequent tests with a given patient.

- 'Make' Test: An isometric test where the patient exerts their maximum force against a dynamometer held in a fixed position by the tester. The device measures the patient's peak voluntary force output.

- 'Break' Test: In this method, the clinician applies a steadily increasing force against the patient's limb. The device records the force at the moment the clinician overcomes the patient's resistance, or "breaks" their hold.

Research suggests that 'make' tests may offer higher reliability than 'break' tests. This is because 'make' tests are dependent solely on the patient's maximal voluntary effort, whereas 'break' tests can be influenced by the tester's own strength and technique, introducing potential variability into the measurement (1).

Can I Really Use a Single Force Plate for Both Balance and Jump Testing?

Absolutely. This is a key advantage of modern, high-quality portable force plates. The same hardware is engineered to handle a wide spectrum of assessments, from minute shifts in balance to explosive, dynamic jumps. For balance testing, the plate measures microscopic changes in the center of pressure.

For jump testing, it captures macro-level metrics like peak force, power, and rate of force development (RFD). The distinction is managed by the software, which should have distinct, easy-to-use protocols and analysis tools for each type of test. This versatility makes a single force plate an incredibly powerful and space-efficient tool for a clinical setting.

References

- Hébert LJ, Maltais DB, Alméras E, et al. A systematic review of the reliability of the 'break' test and a comparison of the 'make' and 'break' tests for measuring knee extension strength with a handheld dynamometer in children. Physiother Can. 2011;63(4):426-435.

At Meloq, we design accurate, portable digital tools like the EasyForce dynamometer and EasyBase force plate to help you replace subjective guesswork with hard data. Our ecosystem is built to streamline testing, speed up your workflow, and get patients more engaged through clear, repeatable results. Explore our devices and see how you can elevate your practice.